How we learn to recognise problems (long-read)

Why just telling 'focus on the problem' isn't enough

In the last edition, you all voted for this topic. So you did this long read to yourself. Happy now?

⚠️ Warning, you can’t apply this post directly to fix your startup. This post aims to boost you general thinking. If you are not interested in that, here are 20 chat GPT prompts for founders.

How many chairs are shown in this gif?

Let’s start interactive, that way I don’t lose people who don’t like reading. Easy exercise: how many chairs are shown in this gif?

Take your time to count them. It’s 3 seconds each. Gut feel: chair or no chair?

I often kick off a lecture with this exercise. People are a bit confused at first, however, everyone has an opinion on what a chair is and what is not.

More often than not, hefty debates spark loose. Last time, in a suburb of Eindhoven, a young aspiring creative shouted “Come on! That’s not a chair. If that’s a chair, my lap is a chair, Jesus!!”

I asked the class: why do you think I did this exercise? Common answers are

Everyone has a different idea of what a chair is

The function of an object can be used to define it (something to sit on)

Cultural backgrounds might influence what constitutes a chair

We will never agree on what is a chair

These are all valid. I’ve done this lecture with hundreds of students. And nobody ever reflected on the following thing: why do you have such strong feelings on what is a chair?

Somewhere, in that creature that we are (avoiding the mind-body problem), we’ve got something that helps us to detect what a chair is. All students so far have a chair-detector, it seems. That detector is what scientists call ‘concepts’.

What is a concept?

From a scientific viewpoint, we have a relatively mild understanding of how our mind works. From a philosophical point of view, it’s even harder. I’ve once tried reading philosophy of mind and I can tell you: if you ever want to feel stupid, pick up something like that, it’s one of the most abstract things I’ve ever read.

Everything in this section is a way of explaining how we humans work, and by no means I’m trying to say that this is how it actually works. I’ll leave that to the scientists on this matter, but the following I’ve found to be helpful explanations.

A chair is a concept that lives in our mind, psychologists believe. If you’ve studied psychology, this might not be new to you. Concepts are heavily debated, because, we don’t know if they ‘exist’.

I can point at a mountain and say: Look at that mountain over there. And you can confirm that there is a mountain, as you can see it yourself. I’ve even got the picture to prove it.

But that idea of a mountain, does that exist in a similar fashion as the mountain does? Here we get explicitly philosophical. And it’s complicated for science because we can’t measure that idea of a mountain.

But, for clarity of thought, I like to think about concepts that people use, whether they exist or not. And these concepts help us to understand the world.

For instance, when you were thinking if the exercise gif was showing a chair, you were using the concept chair, but also related concepts: no this is not a chair, this is more like a couch or a stool.

We have these concepts that act like templates that we aim to fit like Cinderella’s shoes around what we are observing. For one image, a couch fits better than a chair, therefore we say it’s a couch. Or loveseat, you name it.

How we learn to recognise chairs

If we go back to the chair example. How many chairs have you seen in your life? If I ask my audience this, most guess some number in the 10.000 to 50.000. Mind you, every plane you’ve been on already has about 200-300. If you ever wandered through a train to find a spot, you probably encounter hundreds.

Ever been to a sports stadium? That’s another 50.000 just there. I think every human being around the age of thirty easily has seen 1 million instances of chairs.

Every time we are exposed to a chair, we train our conception of what is a chair. We are learning what chairs are, as we go. How does that learning process work? I will explain that using Kolb’s Experiential learning cycle.

1. Concrete experience

The first time we see a chair, assumably as a child, we are baffled. Kolb calls this the concrete experience as a trigger for learning. The experience is taking in that new object.

2. Reflective observation

The subsequent step, which happens almost instantly, is a reflection on that experience. Thinking and looking at that chair. “There’s a person sitting on that chair”. Mmm.

3. Abstract conceptualisation

This is where concepts are born. “That new object, is something one can sit on, perhaps? perhaps I can sit on it?”

4. Active experimentation

The child walks towards the chair and sits on it. The experience is sensory, the child can experience sitting on a chair. We use our concepts to do experiments (mentally or physically, whatever creates new experiences) to test them.

And then the cycle starts again. The child gets a new experience, reflects, conceptualised etc.

How we learn

This cycle is thought of to take place every time we are learning things. It combines feeling, watching, thinking and doing. And if you go through this cycle a lot, the ‘Abstract conceptualisation’ phase has been doing a lot of work, building the concept of the chair deeply.

After seeing millions of chairs, the reflection is probably not a very conscious process. But, exposure to the millions of chairs feeds the abstract conceptualisation. Hence, the concept of a chair has been cemented in our brains, due to the many exposures to it.

What is a problem?

I’ve explained what a concept is and how we learn concepts. By exposure to, reflecting on, and conceptualising from experiences we build concepts in our ‘mind’.

Now we need to tackle the final question: How do we learn to recognise problems? What is a problem, to begin with? I often write about problems (1,2,3), but let’s define it formally.

Problems are subjective things: a problem is a label we give to a situation.

How many people, 20 years ago, thought climate change was a problem? Probably less than today. However, the situation we labelled as a problem existed way before that.

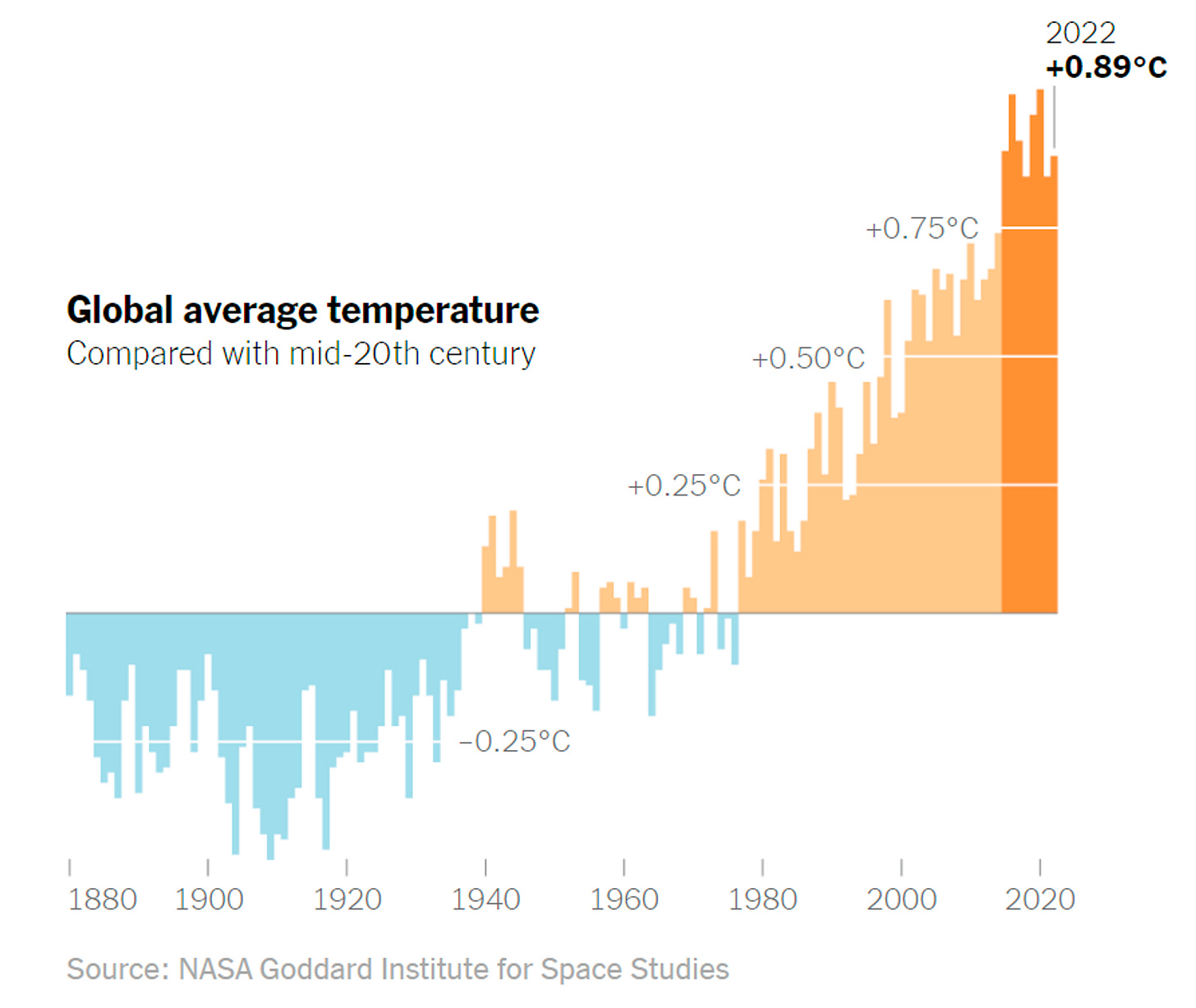

If we look at these graphs, global temperatures have already risen since the start of the previous century and humans had the data. Even after being exposed to Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006) not everyone was swayed. Mind you, this was one year before the first iPhone was released.

Funny thing, these problems. The heating world was already there. The thing changing — besides an accelerating effect — is that more people are classifying the situation as a problem.

What is a situation?

A situation is such a vague word. What does that mean, a problematic situation? A situation is a set of circumstances that we observe. And depending on which problem we are talking about, the circumstances required to define the problem change.

As of today I’m writing this and I’m feeling tired, a lack of energy. I see that as a problem. The colour of the shirt I’m wearing is not important (maybe it’s too relaxed of a shirt), even though it’s part of me today.

Another example is that climate change is such a broad problem. Do you include CO2 stuff in your set of circumstances to classify it, or the rising temperature, or both? Whatever works. There is no finite definition of a particular problem. This makes it hard.

A chair and a problem are not similar things. One is an object, the other is an opinion about a situation. Even though what constitutes a chair and a problem are both subjective, one is arguably more concrete than the other.

Furthermore, a chair is a physical object to which we can point. Pointing to problems can be more difficult. Can you point to climate change for me? You can point at concrete manifestations of the problem, such as increasing wildfires, but that is not the full problem of climate change.

Yuck, this is a messy bit.

Identifying problems and subproblems

What is important about problems, is that they don’t come alone. It’s a negative assertion of a situation, which implies that the observer imagines desired and preferred alternative situations. A problem is a starting point of an investigation of a better situation than the current one.

Problems are hard to recognise since they are extremely situation-dependent. A chair is always something one can sit on, with some vague constraints, regardless of where you are.

Problems on the other hand are unique to each situation, cause each situation has a unique set of circumstances.

If a problem is a set of circumstances that we classify as non-optimal, the recognition part comes two-fold: we require ideas of better situations, and we require ideas of sub-optimal circumstances.

Let’s imagine you are a dietician and you are meeting someone who is obese (who wants to lose weight). You feel like there’s a problem (being obese) and an idea of a better situation (one with less weight). However, that’s like a summary of the situation.

What causes this patient to be obese? This is how a problem inquiry starts. The dietician will likely check the consumption patterns of the patient and will have a keen interest in the activities the patient does to stay fit.

Let’s say the patient eats too much and doesn’t have a physically active lifestyle. We can classify those two as problems. Why?

Because we’ve been exposed to these problematic circumstances before. Most people know that you get fat if your daily calorie intake exceeds what you use: these excess calories need to go somewhere.

Based on our prior knowledge of what are ideal situations (not being overweight), we are able to recognise this situation as problematic. Our prior knowledge then helps us to identify perhaps two areas of inquiry, namely activity and consumption patterns.

So the concepts of weight, physical activity and calorie intake help us in classifying a situation as a problem. This is why training a doctor takes quite a long time: a theoretical study of problems (diseases), causes and mechanisms and apprenticeships in real life to recognise and treat them.

Why is it hard to recognise problems in innovation?

The previous example with the dietician builds on common knowledge of activity and calorie intake. But what happens if someone is obese and all existing knowledge doesn’t explain the extra weight?

Simply put, what if all of our Cinderella’s shoes (or chairs) don’t fit? That’s curious. Because now we don’t know where to look for explaining the sub-optimal situation.

This is what makes innovation hard. Because we are trying to fix a problem that hasn’t been fixed before. Hasn’t been identified before.

We don’t know what the core mechanisms are that require attention. This open exploratory process is non-linear and therefore not for everyone.

Experienced people recognise more problems

This is why inexperienced people make mistakes. For instance, a first-time founder tends to focus on their solution, rather than talking to customers.

They are not able to recognise situations as problematic, because they haven’t gone through the cycle: no abstract concepts exist for them.

After failing to get traction, entrepreneurs are forced to reflect on what went wrong. Building a better conception of what is important is key if you are building a startup.

Scientists have done experiments where they’ve seen that experienced designers tend to spend more time understanding the problem than inexperienced designers.

Research has shown that serial entrepreneurs have richer conceptions of opportunities: This might sound vague, but if I write it as follows it matches this article:

Serial entrepreneurs have been exposed to more situations that contain opportunities and therefore have richer conceptions of what set of circumstances might have opportunities.

So how do we learn to recognise problems?

We learn to recognise problems by being exposed to many problems and understand these subproblems. Through these reflective cycles where we conceptualise based on our experience, we build concepts of problematic s.

Especially deep understanding of the underlying mechanisms that give cause to problems casts a wider net in recognising them, such as the calory intake and physical activity example for the dietician.

Recognising problems is essentially building new concepts by engaging directly in the situation. That’s why problem interviews or observing your customers are important ways of researching, they give you concrete experiences to reflect on and conceptualise problems.

I hope this was clear. If not, let me know.

Want to read more about abstract concepts?

Why would it be difficult to talk to pigeons or check out this book

What should I write about next?

You made it all the way down. Proud of you.

I like the idea but I didn't find the article to be clear.

I feel like the last section was the most helpful but still very high level:

So how do we learn to recognise problems?

We learn to recognise problems by being exposed to many problems and understand these subproblems. Through these reflective cycles where we conceptualise based on our experience, we build concepts of problematic s.

Especially deep understanding of the underlying mechanisms that give cause to problems casts a wider net in recognising them, such as the calory intake and physical activity example for the dietician.

Recognising problems is essentially building new concepts by engaging directly in the situation. That’s why problem interviews or observing your customers are important ways of researching, they give you concrete experiences to reflect on and conceptualise problems.