Competitive matrices are often used to prove product market-fit

However, these things are worth nada when it comes to validation

Here’s why people make them and what’s wrong with them

The MBA-Reflex: competitive matrix

About ten years ago, I did a startup: a digital legacy app that would hand down your bank accounts and passwords to your relatives when you passed away. Ironically, the startup died.

Yet at the start of the journey, to understand the market, I did what any MBA would do: make a competitive matrix.

And what do you know: when I was done, our product would be superior on all identified dimensions. It would have more features, be free, and have more social features than the competitors.

Boy, were we in luck. We had such a great product. We thought.

After a launch peak of 1k people downloading the app, usage flatlined: we made something people didn’t want to use.

The matrices didn’t prove us anything. Actually, it made me falsely believe we had something great.

Unclear axis don’t help

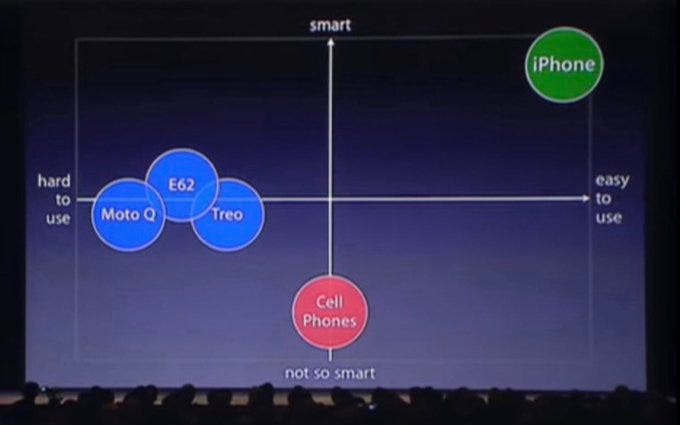

Steve Jobs made one for the iPhone. Ofcourse, he felt his iPhone was easy to use. And super smart. He wanted to communicate that.

Sure, iPhones were easy to use, but we know that in hindsight. The smartphone category was still emerging.

If we would unpack this matrix, quickly it will fall apart. Is the ease of use gap that big? People were using Nokia smartphones and Blackberries.

What does the smartness dimension even mean? It was launched without the app store, which was available 1 year later. It’s nearly not as smart or automated as most of our devices now. Was it truly more smart than the Moto Q?

To conclude, such diagrams might be powerful marketing devices for the uncritical audience, but it doesn’t prove you anything.

They are very product focused

What all of these diagrams have in common is that they do one thing: focus on products or features.

By comparing yourself to the right things, you might always look great. Some incels claim that attractive women sometimes purposefully have a less attractive girlfriend.

I’m not sure about that, but I’ve seen countless pitches where a founder compares himself to products his target group would never choose.

Do you enjoy these types of posts? Consider donating to buy me more time to write these pieces – starting from $2.5 per month.

Better: include the customer needs

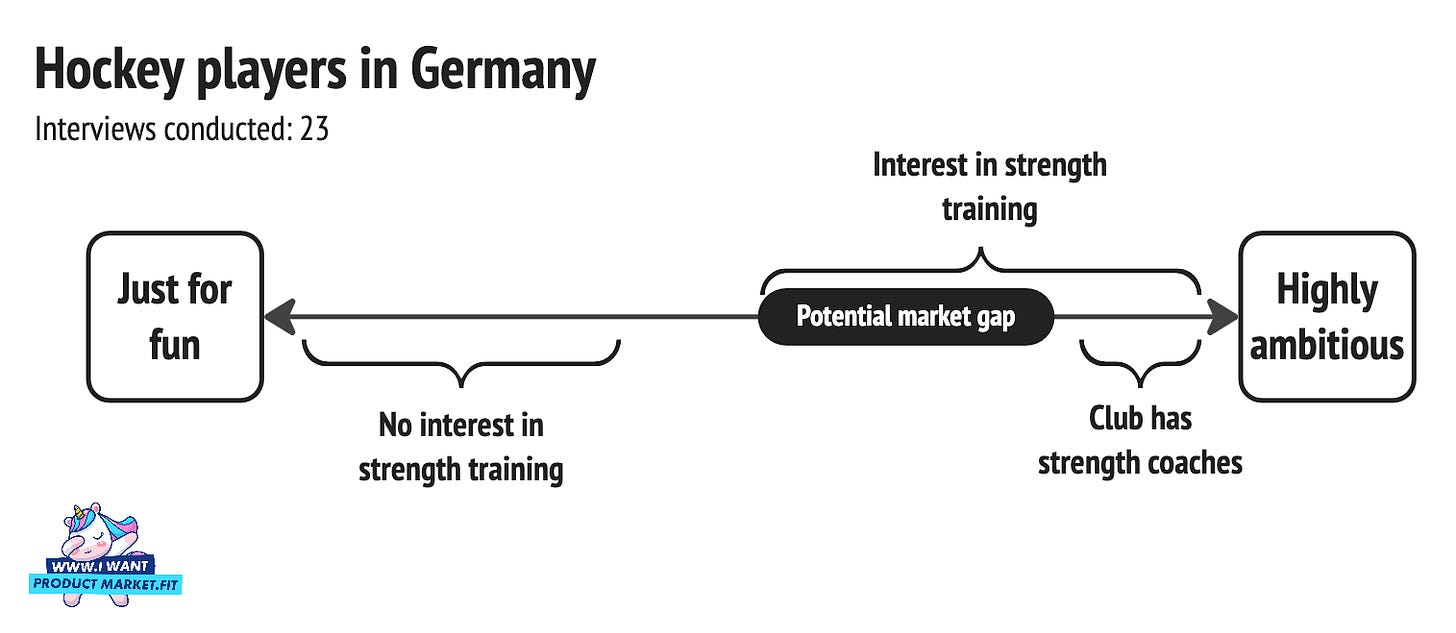

A startup aimed at professional strength training app for hockey had a different approach (I wrote about their experiments to find beachheads before).

A key idea was a market gap they visualised using the customer needs. They found a key dimension for their market was the level dedication to becoming a professional.

For that, sport specific strength training can help, but you require a program. Some professional clubs have coaches for that, yet there’s a gap.

Based on 23 interviews, they saw that there’s a segment of the market that wants to go pro, but doesn’t have strength coaches available.

That is a market visualisation that focuses on unmet needs and competitive gap, rather than features of competitors. Finding these dimensions can be tricky. What dimension predicts sales? That’s the question.

If you can just say how you are more or differently feature packed, I just assumed you don’t fully understand your market.

Conclusion: Timewaster

Only when you are making pitchdecks you might want to consider this as a means to communicate your perceived opportunity. But there are other ways to achieve that.

As an early-stage startup founder, I wouldn’t spend too much time on crafting the right visual. Time is better spent on understanding why your potential customers choose for your competition (ask them), rather than analysing their features.

You need to become the market expert.

I think this is literally THE thing AI research by customers will replace. They'll throw their own requirements in the list and ask AI to generate the matrix to their needs. Interesting how this will change sales and shopping. Even more research - but faster.

That "market gap" always exists for any product or service: (1) No interest in product or service (2) Interest in product or service but doesn't use it for some reason (3) Interest in product or service and uses it.