🎧 This article is a long read! Therefore, I added an audio version! It is also available on Spotify and other platforms.

The adage goes that most startups don’t succeed. To be more specific, 9 out of 10. Is it though? Do 9 out of 10 startups really fail? Let’s settle this once and for all.

Join me on this rabbit hole1.

Bold claims with questionable sources

Ranging from Forbes to weird blogs, the 90% number is everywhere. But where does it come from?

Forbes, even though people think it’s a good name, doesn’t list a source. The Forbes example is not unique.

There are hundreds of blog post posts that aggregate numbers for startups’ survival and performance. This post by StartupTalky is a illustrative example. It gives 111 percentage-based statistics of startups (src: cmd + f - and search for %).

The page by StartupTalky has over a hundred claims of statistics, but none have a verifiable source. Most of these blogs prioritise quantity over verifiability.

Another telling example of this is this blog (screenshot below) by someone who tried to sell me an online business-building course. Not sure if I would buy that course, but given that she was on the first page of my Google Search, I would buy her SEO course.

You would expect this hyperlink get me to the study, right? Right? Nah, it’s just a link to her course. If I Google Search for ‘Nanoglobals 1 in 12’, I actually do find a blog that lists this number, but that blog bases it on something else (more on that later).

I understand these are SEO pages, but still, it was up on the first page of my Google search on the matter, so other people might find this thing too.

So, there are a bunch of numbers of startup failure rates, that all revolve around the idea that the vast majority of startups don’t make it. Where do these numbers come from?

Along the way in this blog, I’m collecting some key mantras for this statistic. This little exploration gives me a first:

Mantra 1:

We need a verifiable, direct source.

Origins of the number

An easy starting point for this investigation is Failory’s article on startup failure. Many of the blogs with sources point to an article/listicle by Failory, founded by Nico.

It’s a newsletter, such as this one, that focuses on preventing startup failure. They have more or less claimed the number as their main marketing message.

Nico provides a nice overview of failure statistics, with sources. All we need to do now is to verify these sources, right?

1. Startup Genome

One of the most often cited sources is a 2019 report by Startup Genome. Startup Genome is an organisation which is known for producing reports on startup ecosystems. They survey popular startup regions, such as Amsterdam and Berlin, and write it up. Fun read.

The 1 in 12 number is different from the 1 in 10 number you often find. The 1 in 12 number seems unique to the Startup Genome report. Every time you see this statistic without a source, it’s probably this. The site that tried selling me that online course? 1 in 12, indeed, ended up referring a source that referred to Startup Genome.

This analysis was made by the founders of Startup Genome, Bjoern Lasse Herrmann and Max Marmer. They mention this number comes from calculations on a dataset they made of 34.000 companies.

They don’t show a lot of insight on the analysis itself. Where are these companies located? Sampled from? Is it just VC-backed startups, or any startup?

I want to trust them, but in the back of my head I hear a voice citing Hitchen’s razor2: ‘What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence’

Mantra two:

We need to be able to verify the calculation to some extent

2. VC failure only

Failory links to an interview with a Harvard Business School professor, Shikhar Ghosh. The statement goes: 7.5 out of 10 VC-backed startups fail.

It links to a paywalled article in the Wall Street Journal, but archive.ph to the rescue. Unfortunately, this statistic is about investments in startups. On Harvard’s own educational website citing the professor we get the same insight that most startups don’t return their investments.

“If failure means liquidating all assets, with investors losing most or all the money they put into the company, then the failure rate for start-ups is 30 to 40 percent, according to Shikhar Ghosh, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School who has held top executive positions at some eight technology-based start-ups. If failure refers to failing to see the projected return on investment, then the failure rate is 70 to 80 percent. And if failure is defined as declaring a projection and then falling short of meeting it, then the failure rate is a whopping 90 to 95 percent.”

Ghosh bases his findings on ‘2,000 companies that received venture funding, generally at least $1 million, from 2004 through 2010.’

A 2013 article in Harvard Business Review states that in the US, only 1% of startups actually get VC funding. And that is the US, the land that is commonly known as the land of getting easy funding.

If we want to give accurate insight to founders, flaunting statistics that don’t cover 99% of the startups, seems a bit odd. Is there data available on more companies than venture-backed?

This gives us two more mantras:

Mantra three:

We need to understand what is included in their definition of startupsMantra four:

We need to understand what their definition of failure is

3. US Government - Bureau of Labor

Failory and other blogs such as Exploding Topics link to an official statistical sheet of the US Government. It’s not a fancy report, but a simple text file that looks like this.

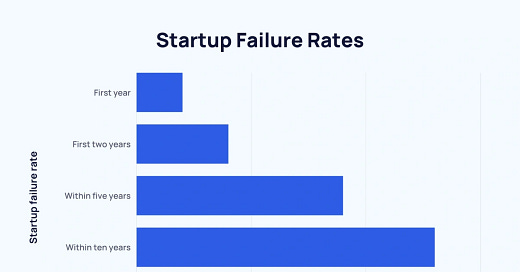

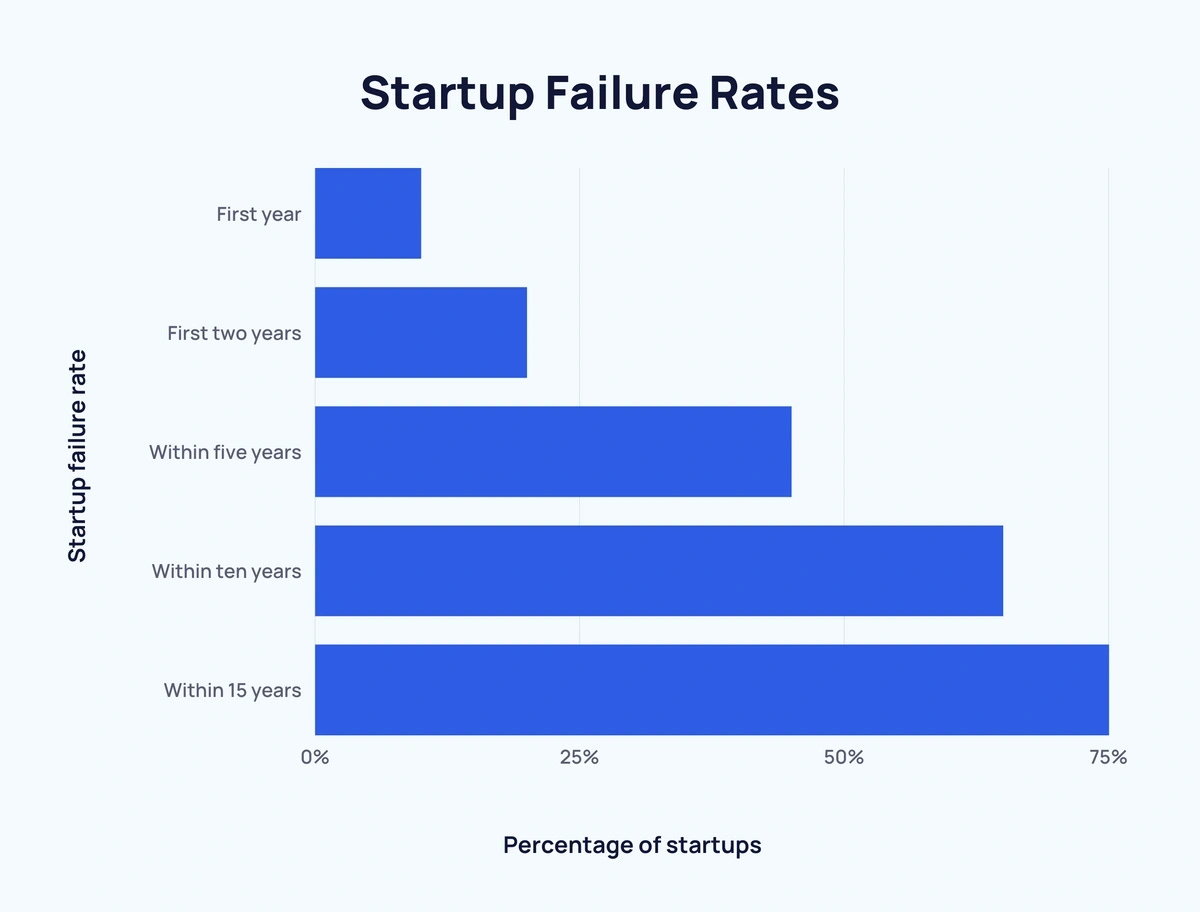

The US Government has tracked new company survival rate numbers since 1994. Exploding Topics made a nice graph out of it, that on inspection seems to overlap with the datasheet by the US government. 15-year survival rate of any business in the US: 25%.

The US government also published a graph, focusing on the early years, with more explanations of where the numbers in the datafile come from (here)

Two takeaways: survival rate drops as the years go by. And, for the US, these numbers seem more trustworthy than the Startup Genome numbers. We don’t see the full dataset behind it, but we get a little more insight in how the number is calculated.

Still, we don’t know everything. This is the US only. And, Exploding Topics makes a simple error: startups and new businesses are not the same thing.

By now, we’ve discovered quite some mantras for our what a good statistic would be:

Mantra one: We need a verifiable, direct source.

Mantra two: We need to be able to verify the calculation to some extent

Mantra three: We need to understand what is included in their definition of startups

Mantra four: We need to understand what their definition of failure is

Let’s unpack those last two first.

Defining terms

For some, the most boring aspect of science: the definitions of things. Why is there not just a single definition for things, that would be easier? Unfortunately, often that’s not how language works.

Therefore, we need to flesh out two concepts: startups, and failure.

What is a startup?

Early in my PhD, I dug into startup failure reasons and rates for my first conference paper. There’s a lot of research out there, and the data’s pretty cool: they randomly dial phone numbers in a country and ask questions like

“Do you intend to start a company this year?”

“Have you started a company in the last five years?”

“Is your business still around?”.

Like election polls, this gives insight into national averages. But there’s a catch: ‘Starting a company’ isn’t the same as ‘starting a startup’—at least, not for most people.

My neighbour opening a hair salon is very different from an engineer trying to solve a particular problem with his MVP and intending to turn that into a scalable business. Both are entrepreneurs, but only one of them is a startup. At least in my book.

Definitions of a startup, like definitions of the term MVP, come in many flavours. However, some aspects get in almost every definition.

Start-up is a phase of a nascent company, so they are still setting up shop and figuring things out

There’s something novel or innovative about it: new product, new technology, new business model

Startups are intended to scale and grow. After product-market fit, companies want to scale and are commonly labelled as a scale-up.

Do you like this type of content? Get me as a keynote speaker for your event.

What is failure?

The Oxford dictionary defines failure as ‘the lack of success’. The lack of success can mean a lot of things in startup land. For founders, it could be not meeting your dreams. Or having to shut down your company. For VCs, it’s not earning their investment back.

To define failure, I need to paint the context for which I’m going to use the number. I work a lot with first-time founders and early-stage startups. I want to give a representative number to these founders, to indicate how hard it is what they are going to do.

Being in business

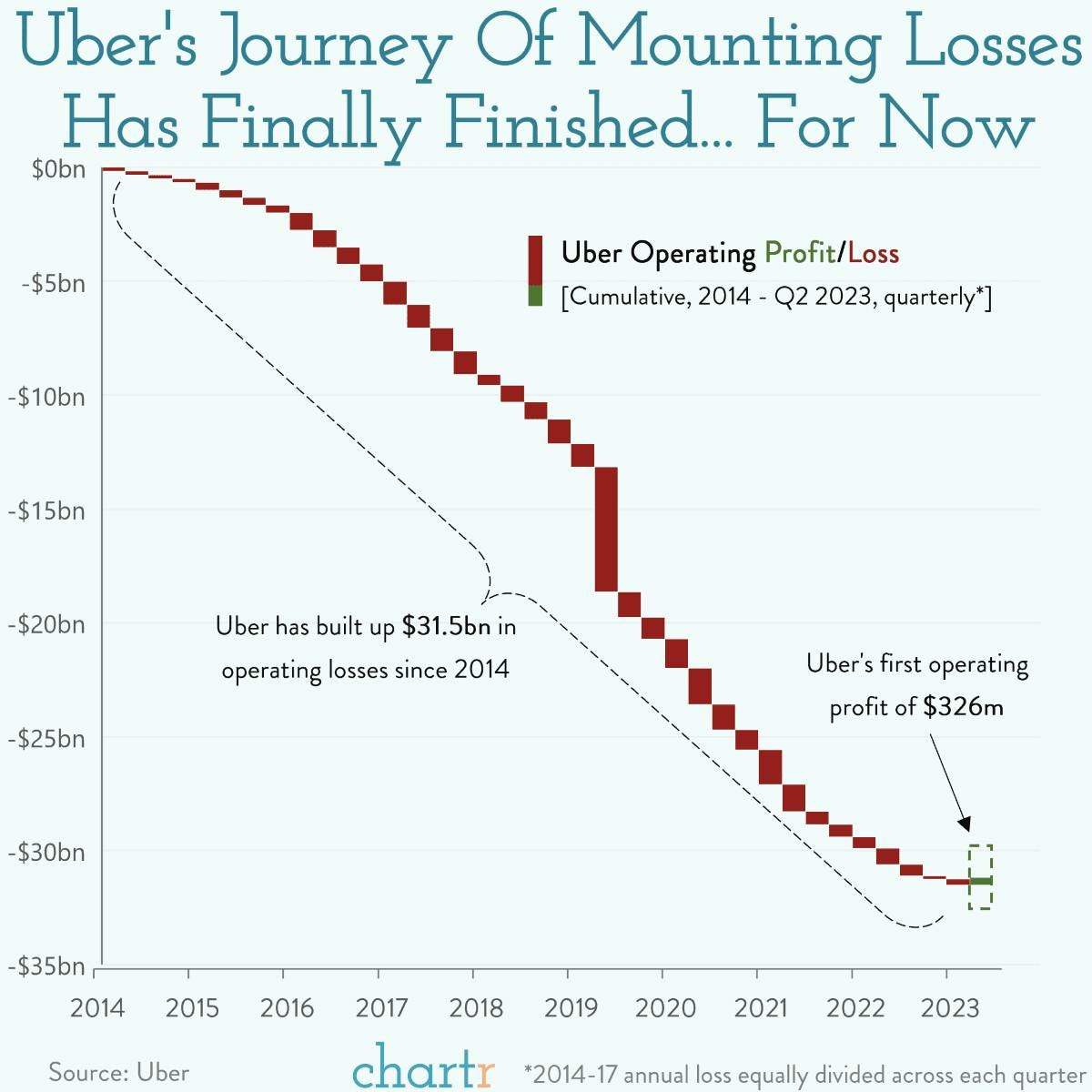

That means, failure should be the opposite of what they (and not VCs) are trying to achieve. So killing your business is failure, and being in business is not? Well, first we need to unpack what ‘being in business’ is. The problem with startups is, that initially, they are never profitable.

Uber (in)famously only started to turn a profit after 10 years of being in business. Were they failing or succeeding before this? That’s unclear. As long as a startup is ongoing, we can’t tell if it will succeed. There’s certainty that if a startup is killed or abandoned by its founders, the odds of it being picked up again are low.

For me, anyone that is serious in doing their startup is in business. That can manifest as writing a business plan, talking to early customers, even though first revenue might by months or a year out.

Is killing a shitty idea a failure?

In my university startup program (Build Your Startup), I’ve now seen 130 startups get founded.

The first cohort started in 2016. Of the first 10 cohorts (BYS1-BYS10), roughly 18% is still in business. To get to this number, I have a spreadsheet with all startups ever founded in the program and yearly inquire with the surviving startups if they are still in operation.

Did those other 82% fail? Hard to say.

Based on my gut, half of the companies that were killed didn’t have a very promising startup idea (which they learned throughout the program). And for the other quarter, the founders were not the most entrepreneurially inclined people, so the amount of customers was low to non-existent.

There’s only a handful of startups that I would’ve expected to take off, were they not killed. So speaking of failure is a bit harsh. I like to speak of either killed startups or abandoned journeys.

There’s also the category of shelved startups: startups that people are not yet ready to kill, because they say to themselves they will pick it up later. This is rare. Usually, it’s stay of execution.

But either way: the startup is not being built anymore. The entrepreneur is the lifeline of the startup. The question is: Is there anyone actively working on this thing with the intention to grow and scale it? If yes, it’s alive. Otherwise, it’s not.

Defining the terms

Startups are new businesses that have something novel or innovative, that are launched with the intention to grow and scale. Startups are alive when someone is actively working on it.

Now, can we find data on this?

The origins of the 90% myth

Quick, to the academic literature!

A source of literature that is generally more transparent than SEO-oriented blog posts is academic literature. A 2011 chapter in an academic book titled ‘The new venture mortality myth’ takes a critical stance:

“Official statistics tend to exaggerate enterprise churn, and it is common practice to assume that enterprise discontinuations are failures”

It underpins my hunch that indeed, not failures are ‘bad’, and that these numbers can be exaggerated. The funny thing is, I discover the 90% myth here:

Impossible claim given the available data

In short: It’s not 90%. But that myth has taken hold of the public. In a survey of the UK, most people, especially those involved with entrepreneurship, are aware of the myth (Allinson et al., 2005).

There’s one source to the 90%. According to the screenshotted article above its by Dun & Bradstreet in 1975. What did they do?

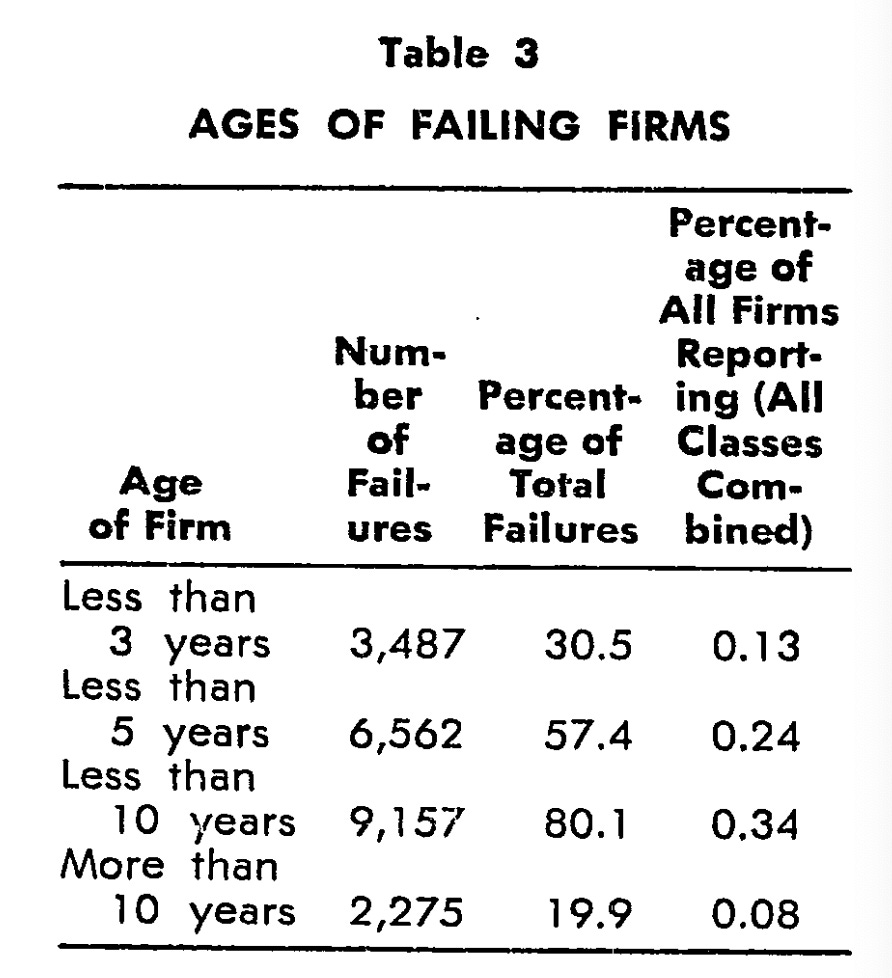

Dun & Bradstreet analysed 11.000 venture failures. They tabulated a lot of data. And journalists ran away with it.

In 1978, Michael Massel reflected on what happened there, to find what went wrong. He finds, that that 90% is nowhere in the paper. The report by Dun & Bradstreet tells us something about the ages of companies that failed in 1975.

But, this table doesn’t make claims about the relative survival rate to company age. It appears that after a phone call with Dun & Bradstreet that “[D&B] had no data that indicated the total number of firms in each age group”.

Therefore, it is impossible to make claims about survival rate per age group. Furthermore, this data was not available in the US to begin with.

If anything, the Dun & Bradstreet report showed that with 2.5 million companies in the US, and only 11.000 failing in one year, there’s a 0.43% chance of failure. Not exactly 90%, Michael Massel reflects.

Note that compounding survival rate seems not to be considered by Massel.

So what is it then?

Well, you can find out yourself. OECD keeps data on this, and after playing around with some filters, I found these survival rates per country:

This gives us some idea, that the range of survival rate in some European countries is between 75% and 95% for the first year, and between 35% and 60% for 5-year survival rate. These numbers correlate with what we’ve seen in the US, earlier in the article.

✅ Mantra one: We need a trustworthy, verifiable, direct source.

OECD is trustworthy in their numbers✅ Mantra two: We need to be able to verify the calculation to some extent

OECD allows you to play around with the data. It also offers a report on how they calculate it.❌ Mantra three: We need to understand what is included in their definition of startups

We can select time, region and industries. But, we can’t filter on startups✅ Mantra four: We need to understand what their definition of failure is

In the above report, they define it very precisely.

So this source checks 3 out of 4 boxes. Can we say something about all new businesses? Yes. About startups specifically? No.

Enjoying this? Consider supporting me, starting from €2.50 / month

What about startups, then?

Plenty of reports and studies lump together ‘any new business’ with ‘startups’. OECD is not different. Even though some firm categories exist in their selection tool that might hold startups, such as ‘Professional, scientific and technical activities’, I can’t be sure.

I assume innovative startups have a lower survival rate than normal startups. A lot of new businesses just copy old ones. Most hair salons are pretty much the same. Not saying it's easy—starting any business is tough—but the business model, value prop, and services? Nothing groundbreaking.

Now take an innovative startup: Pieter Pot. A packageless, storeless supermarket that delivers groceries in glass jars. They did something new. Many aspects were an innovation. But opening a hair salon? Most of the groundwork is already done.

That is my hunch. But when I try to zoom in on innovativeness of a new venture, findings are conflicting, as this 2020 literature review sums up:

So, innovativeness either increases, decreases, or has no effect on the startup survival rate. Ah, ofcourse. Any of the three potential options.

New technology ventures (NTVs)

Luckily, to soothe my disappointment, I found one of the best type of academic titles. A wordplay followed with the actual title.

But, I found a term that might shed some light on the topic. New Technology Ventures. Ventures that inherently have a new technology at heart. This doesn’t include all startups, cause some innovations are not technology but processes or business models. But at least might give us some idea of how much higher or lower.

A meta-analysis from 2008 shows us a 4-year survival rate of 36% and 5-year survival rate of 22%. This is for companies with more than five full-time employees, only New Technology Ventures, in the US, between 1991 and 2000. So again, we know that after 5-years, the survival rate is about 20% to 40%. Slighlty lower than what we saw earlier.

It seems to me that the term ‘new technology ventures’ was popular between 2000 and 2015-ish in academia. Most publications are around that time. There are trends in academia, perhaps this was one of them to describe startups? (Not an expert on NTV).

Distrust any number

I set out this journey to answer where the 90% failure rate came from. We discovered that the 90% number is based on nothing. We found a whole set of other numbers, that described particular survival rates.

Some researchers identified this problem in early 2000s. In 2009, articles predicting that 50% of companies go out of business in the first year were very popular.

But, getting a satisfying answer to the question ‘What is the survival rate of startups in general?’ is harder. Based on above, it actually is quite unlikely that it is 90% that dies in the first year. 50% seems already high.

Apples and Oranges

You can expect most startups to survive that first year, and only after five years, you might see that serious portions fizzle out. But any aggregate number will not be useful for your comparison.

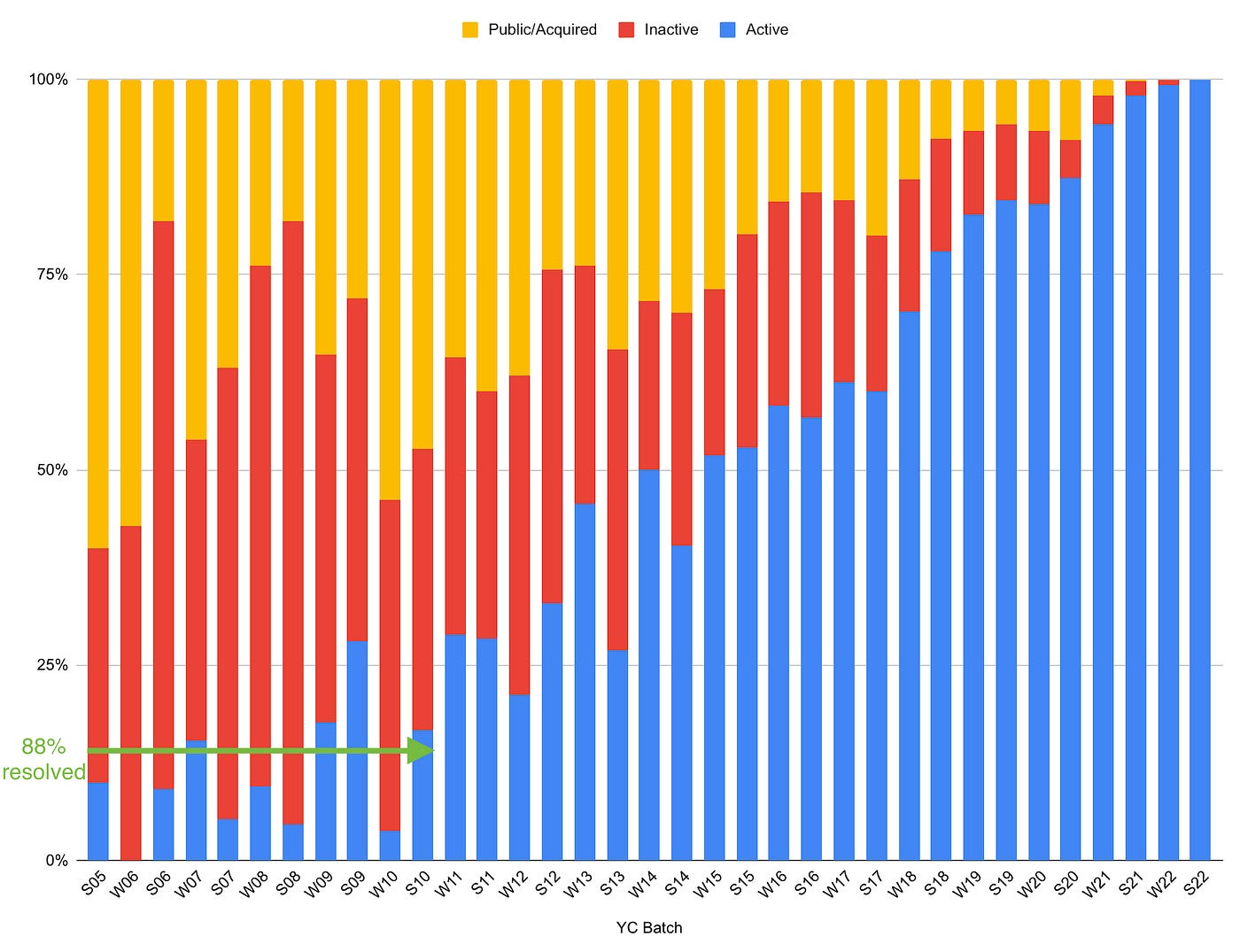

The average startup doesn’t exist. Which startups? It depends on how you group them. My student-based, pre-incubator program has a survival rate of 18%-20%, depending on the time scale.

YCombinator has a short-term survival rate of about 70% - 80%, depending how you measure (and who measures). Long term (after 12 years) it comes down to the below image, with 50% being active (or acquired) and 50% has become inactive. Roughly a 50%-50%. YC is outcompeting the general trends, hands down.

So what? Don’t get hold up on that number.

Summarising

In short, I don’t have a good answer to the question ‘which share of startups fail’. Predominantly, because it’s an ill-formulated question. It leaves out some many aspects that it becomes almost impossible to get the right data to give an answer.

However, this is what I learned.

We can refute the 90% claim. It doesn’t arise anywhere in my investigation so far for 1-year or 5-year survival rates.

First-year survival rate can be up to 90%

5-year survival rate is somewhere between 20% and 50%

Now that we know this. What can we do next? You can roll your eyes whenever somebody drops the statistic. And that’s about it.

Yes, I know it’s long, that’s why I included an audio version.

Shoutout to Els Philip - Remijnse who tagged me in a LinkedIn post of Gideon Barker, who set out on this investigation too. It reminded me of a time couple of years ago I went down this rabbit hole. It was the trigger for me to accumulate my thoughts, once and for all!

Yes, I cited Wikipedia here. Sue me. It’s a great starting point for people unfamiliar with something. Plus, it contains sources to the origins of the saying, which with quotes as such, are often disputed.