Uniqueness bias: “We’re different” is usually a delusion.

Overlooking look-alikes can cost many months and much cash.

New research reveals exactly how this bias blinds people.

Learn how this can supercharge your startup.

The Uniqueness Bias

In How Big Things Get Done, Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner distil years of research on ambitious public works—bridges, high-speed rail, power plants, and the like. The vast majority of megaprojects blow past both their budgets and their deadlines. But that’s just the warm-up, not the book’s real payoff.

Every country has horror megaprojects with serious overruns. The book is not about that observation, but about showing the underlying causes. One of my favourite reasons the authors give is the uniqueness bias. It applies to entrepreneurs, too.

“This time it’s different”

The uniqueness bias is a tendency for people doing megaprojects to believe the endeavours are so unique, they can’t learn from others. “This time it’s different”. Everyone does this.

Even Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking Fast & Slow, and Nobel Prize winner. He’s generally seen as one who put behavioural economics on the map. He should know biases, for sure. He fell for it.

He and his colleagues were writing a textbook for education. They estimated roughly two years to finish it. Only one of the colleagues had experience in such an project and said: This never gets done below seven years. Quote:

“We should have quit," Kahneman concluded years later. Instead, after a few minutes of debate, they carried on as if nothing had happened because the forecast "seemed unreal". Their project felt different, according to Kahneman.

In the end, the textbook took eight years to finish.

Highly unique → Extreme cost overrun

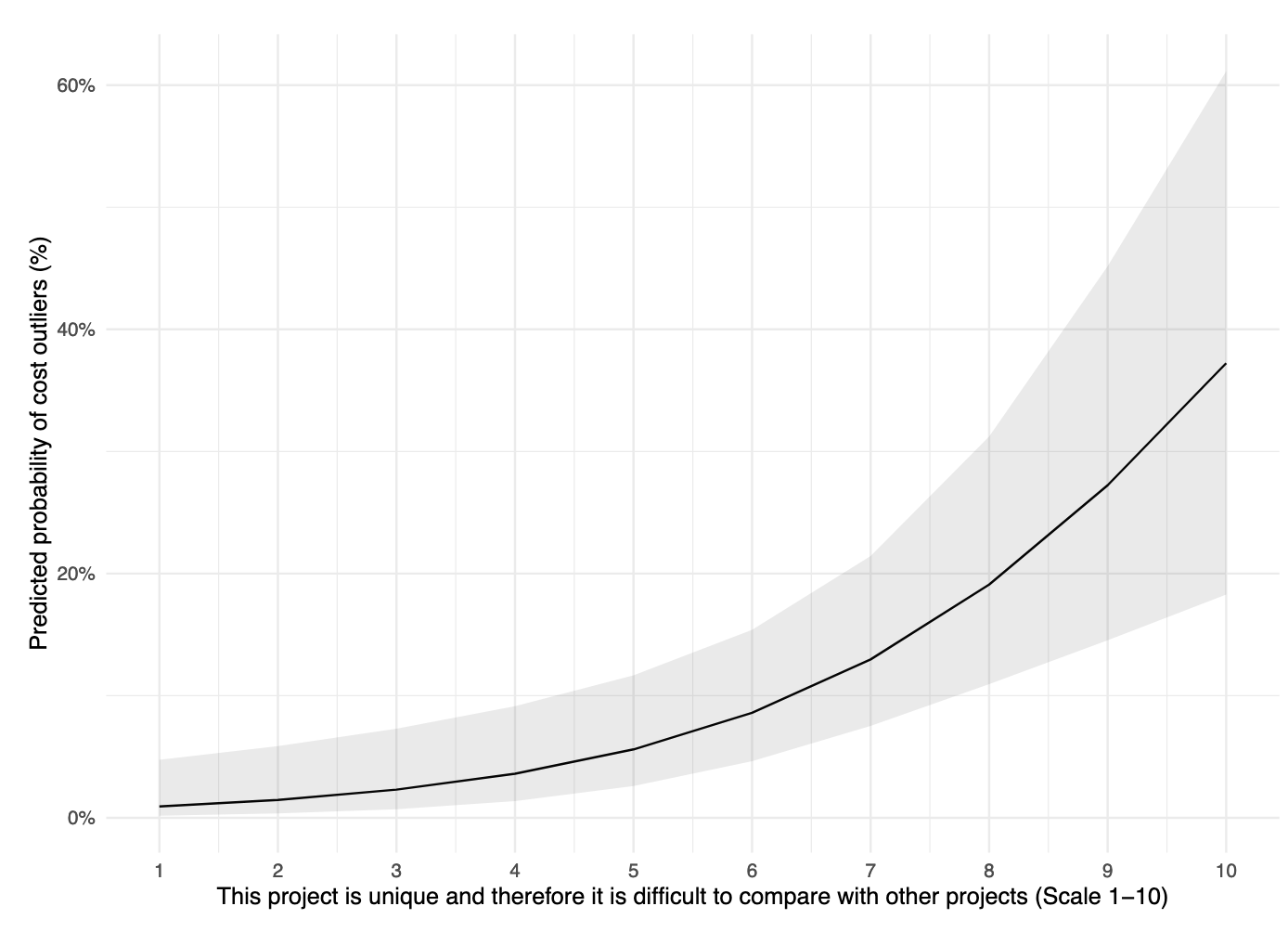

From anecdote to a proper investigation. In a study, Bent Flyvbjerg, Alexander Budzier, M. D. Christodoulou, M. Zottoli, surveyed 216 big IT projects around the globe and interviewed the leading managers on how unique they felt the project was. They asked:

On a scale from 1-10, indicate the following:

”This project is unique, and therefore it is difficult to compare with other projects.”

Perceived uniqueness correlated significantly with cost overrun on a project. Projects judged to be extremely unique—scoring a 10 on the scale—carried a 37 % chance of a severe cost overrun, defined as needing more than 76 % above the original budget. Compare this to 1% of the projects rated as having low uniqueness (1 out of 10).

Do you enjoy these types of posts? Consider donating to buy me more time to write these pieces, starting from $2.5 per month.

Actually or locally unique?

The above results show perceived uniqueness. What about actual uniqueness? Upon investigation, some of these ‘unique’ projects already showed similarities: “five of them were regulatory compliance projects in banks”. Not all too unique, according to Flyvbjerg et al (2024).

Even beyond the study sample, similar patterns emerge. In the opening of his book, Bent recounts how, early in his research career, he discovered that no global database on megaprojects existed, so he created one. Today, that database, which now holds thousands of projects with detailed statistics on cost overruns and other metrics, provides a valuable benchmark for assessing how truly unique a project is.

They selected the most “unique” projects, rated with 9 and 10 by the managers, 23 in total. This must mean that according to the managers, these were truly unique, new to the world projects.

After going through the documentation of those projects, they compared the 23 to the database they had. They found that for each of these projects, a similar project existed in their global database. It was only unique locally.

Entrepreneurs: grand, unique visions aren’t great

I once reached out to Bent on LinkedIn to ask whether he had studied entrepreneurs and the uniqueness bias. He hadn’t, unfortunately. Still, in my work with start-ups, I frequently see founders fall into the same trap.

The entrepreneurs who believe they are most unique and least eager to learn from other failures, are the grand visionaries. They pitch all-in-one platforms, blockchain ideas with many stakeholders, web3, those kinds of ideas.

They’re convinced their vision—and their start-up—is one of a kind. The solution they envision is intricate, with many moving ill-defined parts and stakeholders, and they want to build it all at once, bypassing iterations and validation. As they put it, “I can only test it when everything comes together.”

Interestingly, in the same study on uniqueness in big projects, the authors show which factors contribute to the uniqueness (table above). Three stand out for entrepreneurship: complexity, unknowns in the solution, and having an incremental approach. Doesn’t that sound familiar with the issues I raised above?

In an interesting study from 2020, researchers compared how four founders approached the exact same business idea: Uber for short personal flights.

The founders who were most realistic, had an incremental approach, and focused on complexity reduction, got the best business results. Yet in the end, all companies went under. The idea in general is hard to pull off.

A graveyard to learn from

Here’s my routine on mentoring calls: I let the founder pitch, then I open Google. If page 1 is already crowded with cousins of their idea, I ask, “Ever bumped into X or Y?”

If the answer is “no,” alarm bells. Five minutes of searching saves five months of burn. Scroll through the first five pages, dig up the graveyard, and read the headstones. What did they build? Where did they stall? Learn the lessons.

One mentee was itching to pivot his B2C play into B2B. I put him on a call with a founder who’d already face-planted trying the same shift. Thirty minutes later, he shelved the pivot and poured all energy back into his B2C engine, right as traction was climbing anyway. Net gain: months saved, focus sharpened.

Uniqueness is overrated

Stop worshipping “original.” Survival > uniqueness. Yes, Steve Jobs and his iPhone are unique. For profitability over growth, I say “assume you are not Uber”.

And perhaps similarly, for uniqueness, you can assume that your product might not be as unique and impactful as the iPhone. Those are truly outliers. Comparing yourself to outliers can be the thief of joy.

I meet too many founders who are feeling down because their startup’s revenue is not hockey-sticking like Lovable or Cursor. Only take inspiration from it, but don’t copy the ambitions too literally.

If you want to be praised for being unique and original, maybe become an artist. Customers don’t care if you are unique. They care that you solve their problem better than their current options.