Why it would be difficult to talk to pigeons - part 2

How serial entrepreneurs outperform novice entrepreneurs, a peak into our mind and 4 tips on spotting more opportunities.

Reading time: ±10 minutes. (next edition will be much shorter)

Last week I left you on a cliff-hanger. If you don't know yet why it would be difficult to talk to pigeons, you can check part 1 here. Part 2 is readable without having read part 1. But part 1 is really good so I still urge you to go there.

For part 2, we zoom in on how our mind works and how it relates to startups.

By the end of this piece, you understand:

How we unknowingly misinterpret situations

How serial entrepreneurs are better at recognising opportunities than novice entrepreneurs

How to spot more opportunities

Why it would be difficult to talk to pigeons - part 2

The proposition of my dream

In 2014, a friend set me up with a serial entrepreneur, let's call him Frank. Frank was almost 40 and had a track record in digital businesses. I sat in his office, set in a repurposed old hospital, including bean bags, a pool table, you know, the whole shebang.

I was thrilled with this, as it resembled what I found cool about 'The Social Network' which came out in 2010. I wanted to catch that new mobile wave and Frank might be able to help me with that.

Frank started out as a reseller of some premium .mobi-domains. He built a mobile app agency next to his TV guide app with millions of users with serious monthly ad revenue.

He had a curious way of talking—read the following in a whispering voice—where he sometimes quite artificially would lower his volume that made me listen harder.

Frank shared his vision with me for a new app, which he planned to launch as a startup. He pitched an app where you can keep personal information in a vault, only to be shared with your loved ones when you perish. A digital legacy. Think of passwords, who to invite to your funeral and funeral song requests. He scouted the market and there was no app-based solution out there.

It was a different time than today. Tech behemoth Google was worth 'only' 1/5th of what it is worth today. The iPhone 6 was released that year. 2 years ago, Instagram was acquired by Facebook for $1 billion dollars. I remember how everyone lost their shit, we called it ludicrous. Little did we know that in 2014 WhatsApp would be acquired by Facebook for $20 billion dollars.

People did not realise where this market was heading. I knew one thing: I was willing to be the next in line for insane acquisitions.

He asked me (not whispering): 'Do you want to join this startup as a co-founder with 33% equity?'

Care to take the wheel?

Before we continue, I want you to partake in this experiment.

Picture this. You are in a car in a driving simulator. You are instructed to:

take a left when you see the letters AA on the screen in front of you

take a right when you see the letters AB on the screen in front of you

You start driving.

AA, left.

AB, right.

AA, left.

AB, right.

After a while, you get the hang of it. Then you see two new letters popping up.

CD

What would you do?

You hesitate, you don't react.

CC

Wait a minute.

CD

What would you do?

Same, but different

This is one of those 'there is no right or wrong answers' types of questions. I discovered this experiment in the now-famous pigeon chapter. The experiment helps us to understand the way we think.

If you said 'take a right', you are like a big portion of the people I told this experiment to. You figured out an answer. How did you arrive at an answer to go left or right? Well, you probably saw a pattern. This pattern is an abstraction.

Humans are able to recognise things that are a little bit different, but similar to each other on an abstract level. This is what research calls 'same-different'. We make abstractions to recognise things that resemble our experiences using these same-different mechanics. You do this too, constantly.

Driving on the wrong side of the road

Have you ever driven in a country that drives on the other side of the road? It's a very similar situation to what you are used to. Not entirely similar though, cars are on the different sides of the road, road signs are different, yielding rules are different. But we recognise this situation as being similar.

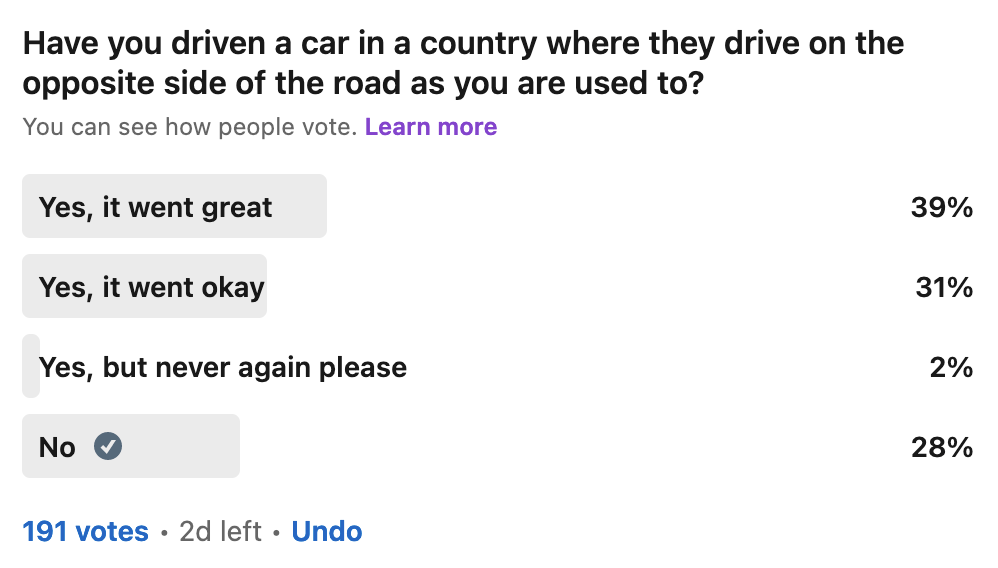

I wondered how many of us were able to drive on the unfamiliar side of the road, but I couldn't find any research on this. Therefore, I conducted a quick poll on Linkedin. I discovered what I expected, but also found something I didn't foresee. And the latter—being sucker-punched by new data—always is the most exciting outcome for a researcher.

In line with my hunch, I found that most people are able to drive on the unfamiliar side of the road. People mentioned that it actually took a little bit of time to get used to, but it was bearable.

If you think about it for a bit longer, isn't that fascinating? We were never trained to drive on the opposite side of the road. Yet, we are able to do so.

We recognise new situations using abstractions from our past experiences. We pick our actions based on these abstractions. This process is not always known to us. Heck, sometimes it takes time to see we are wrong.

The situation can trick us

Take a look at this story from the comments, which surprised me. A commenter was in a remote place in South Africa. He wakes up, takes his car and starts driving. The streets are completely empty. Only 20 minutes in, he sees oncoming traffic. Heading right at him! He quickly realised he had been driving on the wrong side of the road for a full 20 minutes.

Two other commenters shared a similar story on early-morning driving and falling back to your old habit.

It seems, without orientation, we fall back in our old habits. Without the clues, we don't recognise the situation as same-different; we recognise our situation as the same as back home. Context helps us in understanding what we see. And if we don't see anything different, we assume it is no different.

But what if you can't see it's different?

I'll show you that with an example from the field of artificial intelligence (AI). Herbert Roitblat shared the above picture with me. He is one of the scholars that helped me out in the pigeon part 1. He furthered his career in the field of artificial intelligence. In this picture, a computer vision model (AI) tries to identify objects.

You probably can confirm that the big object definitely is an airplane. However, the small object… That’s definitely not a kite, right? It's a toaster (high as a kite). It was purposefully photoshopped there to confuse the model.

The model was not able to recognise the toaster next to an airplane. This is because the model did not have experiences (training data) that resemble toasters in a sky, let alone toasters next to an airplane.

Therefore, it mistakenly assumes it is something else. A kite, because kites among the sky assumably were in the models training data. Same-different went wrong. It's not the same. It's a toaster.

We humans are not AI models, but we share same-different mechanisms with AI, as Herbert Roitblat explained to me.

If we recognise the situation in the wrong way based on our past experience, we might apply the wrong tools. And that explains part of my startup failure.

Getting the situation wrong

Back in the repurposed hospital.

Soft speaking Frank looked at me for an answer. Do I want to join that man's startup? I had little sense of building a business unless filling in a business model canvas counts.

However, I designed and prototyped many products in my education on product design. For instance, I created a Twitter-embedded picnic table or a flexible controller for lighting systems for open offices. I freelanced since age 15. Maybe I can do this?

Since I was young, I wanted to be an inventor. I had a dream to launch an app. I saw that they needed someone to help to turn that idea into an app concept. I could do that.

So I said: "HELL YEAH!" We shook hands.

Suddenly, I've got 33% equity and I'm only 23. Oh boy, I'm like Zuckerberg. I'm rich. Almost. It felt like the most value I ever owned. I wanted to become a successful entrepreneur as soon as possible. Launch as soon as possible.

I did what I knew: I opened my designerly toolbox and went to work.

After some months, I arrived at an app concept. Together with a UX designer, front-end and back-end developer a v0.1 was build within a couple of months. Frank spent around €50k-€100k (hindsight estimate) to build a fully working iOS front-end, back-end and web app. Check out this 55-sec video that pitches the app, to get a flavour of the app.

After launch, we got about 1000 downloads. 100% of users churned with a week. Revenue to date: €0, of which I owned a whopping 33%. Luckily it was not my money that paid for the development of the app.

Months later, the app—that was aimed to help your loved ones after you die—died.

Startups are complex things

So, what happened? Let's look at it from the situation recognition perspective.

23-year old, inexperienced Jeroen didn't recognise the full situation.

During my studies, I encountered a lot of situations in which designing a product is a relevant action. Therefore, over time, I unconsciously developed the abstract concept of what a product design situation looks like.

When I joined this startup, I recognised this situation as a product design situation. Hence, I would design a product. Which is not necessarily a bad thing.

Still, I know now, startups are more than the product. You should get many things right to be successful.

I didn't have a rich conceptual library of the many things a startup should have. The lack of my experience results in the lack of abstract concepts that I could recognise. And I didn't realise this until it was too late.

Therefore, I spend most of my time on what I could recognise: the product. This resulted in that we shipped something that was incomplete in nature. The traction and revenue results tell the rest of the story.

Serial entrepreneurs have better concepts

If experience grows abstract concepts in your mind, are experienced, serial entrepreneurs better than novice, first-time entrepreneurs?

Well, yes. But not necessarily on business performance (revenue). This surprised me.

I searched for studies on serial entrepreneurs and the results are contradicting: some say serials outperform novices, some say the contrary. I emailed some of the authors, but I could not formulate a definite answer. Which seems weird, you would think that science has a definite answer on something like that?

Serial’s got game: spotting opportunities

Research does show that serial entrepreneurs are better at recognising opportunities.

An opportunity is a thing that drives entrepreneurs, something lucrative to chase to build your business around. Without an opportunity to create (and capture) value, there is no entrepreneurship.

Serial entrepreneurs recognise more opportunities than novice entrepreneurs. Or phrased differently: Serial entrepreneurs can recognise more situations as containing an opportunity.

Therefore, we could say that serial entrepreneurs have nourished the opportunity concept more than novice entrepreneurs. Which is not surprising. But, it doesn’t stop here.

Not just more, richer too

In a different study, they interviewed 43 entrepreneurs on opportunities, with varying experience, some had a 25 record of businesses. They found that serial entrepreneurs had a richer way of talking about opportunities, meaning that they could identify opportunities in more diverse ways. Again underpinning more developed abstract concepts.

It's not about having more information

Serial entrepreneurs are not better at recognising opportunities because they have more information available. A study surveyed novice and serial entrepreneurs on the amount of information they used. No difference was found.

Summarising: Serial entrepreneurs recognise more opportunities and they are more diverse. And they do so because they have better abstract concepts of what opportunities are. If you want to beat them, you nourish your abstract concepts. 4 tips on this are below.

How to beat serial entrepreneurs

Tip 1: ‘Breadth of experience is breadth of transfer’

I got this quote from the book Range by David Epstein. It found that if you are learning something in a broad array of situations and experiences, you can more easily transfer it to other contexts. Imagine yourself in the driving experiment again. All of a sudden, you see the letters EF. Get the gist? You know what to do know, don’t you?

Expose yourself to many situations with opportunities. Therefore, you need to follow the next tip:

Tip 2: Do your 2nd venture fast, it doesn't matter whether you've failed

Become a serial entrepreneur. It doesn't matter if you failed before. Research tells us that your learning of your first startup will benefit your 2nd attempt, regardless of your success. However, you should not wait too long between your attempts. If you wait for longer periods (2-3 years), your benefits of being a serial entrepreneur evaporate.

Tip 3: Same-different is not your enemy

In this podcast, Steven Levitt (author of Freakonomics) talks about his class where he used two marketing experiments of Budweiser as an example. Years later, he ran into a student that liked the class. However, the student said he couldn’t use it in his job. He worked in marketing for a soft-drink company. Steven was baffled. For this student, it was not a same-different. It was different.

A lot of the opportunities out there are about inserting something that works in one industry to another. It's about recognising the situation on an abstract level and realising similar mechanics of Uber for cabs might work for food delivery (Uber Eats). Surprise: It did not work well from the start (different story).

Listen to stories of entrepreneurs and especially their failed attempts. The final version of something is not only the final version of something, it is also all the alternatives the founder chose to abandon. Try to understand why this version works. This can help your abstract concepts to grow.

Tip 4: Reflect, together

Abstractions are formed in our minds when we are confronted with experiences. Research on how we learn tells us that these abstractions are generated more firmly when we reflect on our experiences.

Some even say: Only when we reflect, we learn. That is why failure is linked with learning, as failure forces us to reflect. But you can reflect on your wins too.

"Why did it work?" should be asked as often in your startup as "Why didn't it work?"

People will notice different things. Articulating and sharing these reflections with others will help to build your abstractions. Ask your founding friends: “What is your idea of an opportunity?”

Jeroen's take

Fake progress

5 years of design education and 5 years of educating product designers has thought me the following: if you give a product design brief to a product design student, you will get a designed product.

Whether that product is actually desirable, viable or feasible or not, you will get a designed concept. That seems like progress, as now there is a concept when first there was nothing. However, that might not always be the best thing to do.

Shouldn't product designers be educated to design products people want?

Yes. But they aren't in most cases. Students are rarely trained to recognise signals of desirable products. Based on my experience, 90% of their training is in coming up with concepts and articulating them.

Properly testing them for market desirability is something they don't spend too much time on. This is weird, as most products are introduced to people in that way. I know. Barking up the wrong tree here.

On writing this

This was part two of the long-reads that were inspired by the pigeon chapter. I plan to write some shorter ones coming up. It was quite abstract, too. If you struggled with it, that could be positive signals that you are learning new things. Abstract stuff doesn't stick as easily as concrete stuff.

A fun ride, a big detour, I learned a lot and I hope you did so too. I tried to explain everything as well as I could, but it could be that I’m wrong. Let me know if you feel like something doesn’t add it up.

How was this article?

Great - Good - Meh

Any vote helps me, makes me smile like that first day at the disco.

Two snacks for you

John Cleese—living legend—explains why some people don't realise they don't know something

How outdated conceptual frameworks cause stupidity