Upholding customer value during a corona pivot: the true challenge

What can we learn from pivoting startups?

This article is a post-mortem of a well-intentioned pivot of a digital startup, Breeze. I interview Marsha (VP Product) about how this pivot unfolded, as she was most directly involved with this pivot. I reconstruct the story from Marsha’s perspective and verify it afterwards with the team. It’s aimed to simulate the experience this group of entrepreneurs went through.

How do you stay true to your own values during a pivot? What happens if you lose customer value out of sight? How can sudden uncertainty affect team dynamics? When is qualitative and quantitative data convincing enough to make a decision? All these are hurdles startup Breeze encountered during a pivot in times of corona. Enjoy your read.

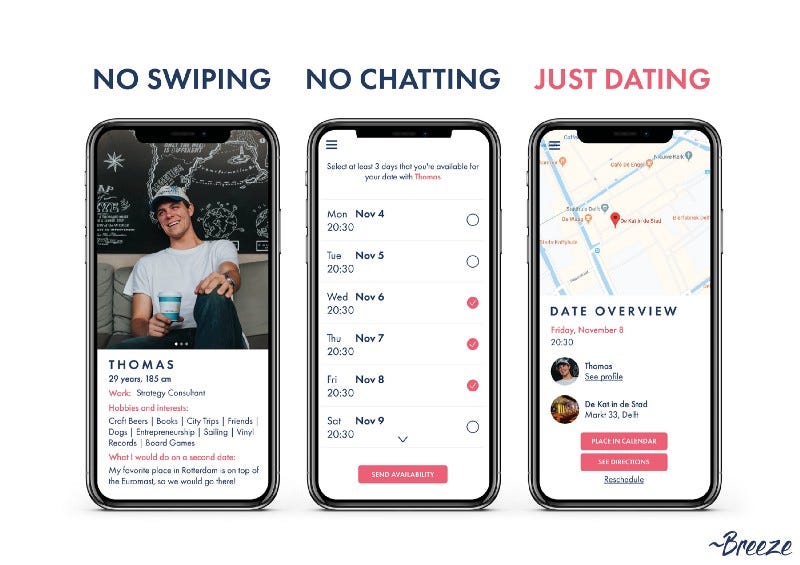

Breeze is a new take on dating. They found that it on average takes 38 hours in apps such as Tinder to get an actual date. In the Breeze app, when both parties say yes to the other profile (i.e. when you match), you plan a date (Figure 2) immediately at one of their selected partnered cafes. You only get 2 profiles per day, which they serve you based on their algorithm. They exchange the time-consuming swiping and chatting with an immediate low key date. They envision to introduce a sense of airiness around dating.

If you have objections to this proposition, you are not the first. I’ve seen them pitch numeral times, sometimes the initial response is a bit hesitant. Any counter-argument that comes to your mind right now might actually be valid, such as “Will people believe it’s safe?” or “Who would want to do that, I want to chat first!” I would suggest looking at the data to get rid of claims without empirical substance. Starting over a year ago, they have been growing steadily towards 7500 singles on their platform. Until March, their growth was smooth with 35 new users every day (57% monthly growth rate), and they were able to monetise on the dates. When you plan the date, you book a place at one of their partnered cafes and pay upfront, first drink is for free.

So far, they organised 550 dates and are pleased to claim numeral relationships came out of this. That does not leave that this app might not be for everyone. Not an unimportant point when it comes to diversification in any industry. Not all products necessarily have ‘everyone’ as a target group and this should not be an inherent problem, as long as there enough customers.

Corona kills the revenue star

An early-stage start-up that is growing at a nice pace. It would be a shame if something happened to them. Then the Dutch lockdown happened over the first weekend of March 9. On Friday first measures were announced, for instance, closing universities, on Sunday evening the full package sunk and immediate closure of cafes was announced. On that Friday, Marsha reflected that not everyone (me included) saw in full clarity what was about to come. Their dashboard showed a steep drop in their daily new users.

The team worried that cafes would be forced to close soon. The cafes were the locations of their dates, this rendered their only source of revenue useless. On that Saturday, they had 10 dates scheduled, totalling 50 ahead in the rest of the week. The team acted on what they thought was the responsible thing to do: to cancel the physical dates. Many users uninstalled the app after they sent the message: “We will temporarily stop offering our service”. The saw the churn rate increase by 250%. Churn rate is the share of customers that stop using your service every month. You want that to be as low as possible.

First iteration: video dates

The daily new user and churn drop made the team a little anxious: “Now what?” This was the starting point of their search in delivering value to their customers. Quite early, the team came up with the idea of dates over a video call. As an onlooker on their process, I consider this the first shape of the new proposition, which will undergo a series of iterations.

Not a lot of time was spend on thinking about how to deliver those video-calls. Instead, that Friday, they sent an in-app message to the 50 singles (at least I guess singles), that had a date planned, asking: “Would you be open to having the date over video-call instead?” Marsha outlines that this proposition was a full hour date that would live in your agenda up to a week ahead. The results were not all too promising. Almost nobody, only 1 out of 50, said yes. Marsha was not surprised by these results. She imagined it would feel awkward and some qualitative responses of customers underpinned that hunch. People said they rather go on a physical date, assuming that it would be possible soon enough.

To confirm this, the team posted an Instagram poll. “Given the current corona pandemic, would you still go on a Breeze date coming week?” 62% said yes. A follow-up question was: “Would you rather replan your Breeze date in a couple of weeks or would you rather go on a video call date?” 84% said replan. “People didn’t really realise how serious the situation was during that first weekend”, said Marsha

Second iteration

A team divided

On Sunday evening, the definitive nail in their monetary coffin arrived by a live press conference where Prime Minister Mark Rutte announced the closure of all cafes. Their first iteration as described in the last paragraph was not very fruitful. Marsha reflects that the context was so vastly different between those two moments: A cafe-purgatory on Friday and a cafe-straightjacket on Monday morning. However, nobody know how long this change would last. Time pressure mounted on the team.

She mentions that at that point, the team didn’t look back at the results to reassess them. The conclusion: “People don’t want 1 hour planned dates” still stood. With the new context, this conclusion could still hold, but it’s important to note that due to the changing context, answers might change if you were to ask again. The team didn’t have the answers, however. When arrived with Marsha at this point while discussing the journey, I asked her: “Then what?”. Apparently, I was not the only one who wondered. Marsha described the attitude of the team on that Monday morning as: “Fuck, what are we going to do next?” Drafting up a strategy is difficult in times like these. Not everyone in the team reacts as well to rapidly changing environments, she told. A split appeared in the team when two strategies of making the most of this new context arose.

One was: Working on the app and platform to have something great for when it’s over. If you have ever spoken to any programmer, he or she might have complained about tech debt or refactoring that should’ve happened. Easily said, it’s the maintenance that should happen at some point but is also very luscious to postpone.

The other one was coined by the more opportunistic people in the group. Breeze wanted to craft something to stay relevant for their customers, and maybe even attract new customers and sustain the growth that they had before the lockdown.

Value by working on tech debt vs. staying relevant for customers, a tricky call. The team settled on two tracks, some were working on the staying relevant part, others were working on improving the app. How do you stay relevant when physical dates are impossible and data suggests nobody wants a video-date?

Conception

During a brain-storm, in what Marsha describes as a Eureka-moment (also: Aha-Erlebnis, creative leap) figured out a solution when someone mentioned speed dating. She reinterpreted the results of the first iteration. People didn’t say no to video dates in general, they said no to very weighty, lengthy and therefore assumably awkward video dates. Video speed-dates was born.

The articulation of the implications of this idea was easy, within minutes they had it all figured out. The concept was that all users would get a message during the day: “At 20:30 tonight, we have a virtual speed date room where you can join with your smartphone. You will get matched with someone to have a 90-second video speed-date. Afterwards, you get the person’s profile and are asked: “Would you like to continue video calling?” After that, you would be sent into a virtual room without any time limits, where they could continue the call and exchange details if they wished. Concept complete.

To make sure they are not missing out on other opportunities, they did an hour-long brainstorm where fun ideas came by, taking inspiration from TV-series such as ‘Love is blind’. About 15 concepts were generated but subsequently killed. All of them were to far away from their vision and it seemed that their implicit criterium was to make the most of the time during corona that can be valuable after corona too. Their aim was to stay relevant during this period, to their customer and to their vision.

A note I want to add is: Evaluation criteria are sometimes hard to set upfront. Nonetheless, the discussion and valuation of all options implicitly hold criteria. It can be a very lucrative exercise to synthesise criteria from what has been said. It will allow for clarity and alignment within the team and it will be easier in hindsight to reflect on the decisions made.

The two groups within the team seemed to be aligned, however, the group that wanted to work on the tech app debt was worried a disproportionate amount of resources would be allocated to something that only has reasoned value. Reasoned in the sense that it lacked evidence. They perceive themselves to be an evidence-based startup, and they had no evidence for this concept. “That’s when we figured we need to build an MVP to get that data”, said Marsha.

A-B-C, (not as) easy as an MVP

An MVP is the simplest version of a product you can build to learn about and from your customers. There are many discussions among practitioners about what is an MVP and what isn’t, I’m purposely steering away from that.

Their idea for an MVP was as follows. The MVP will be a web app which could be accessed by a link that participants got in the messaging system of the Breeze app. After clicking that link, through 4 steps (Figure 6), people would participate in that speed date round (1st screen). In the virtual room, they wait for a match and when a match was found (2nd screen) go to a private video chat (3rd screen) for 90 seconds. After the call, the two daters could select whether they want to continue the video chat without a time limit (4th screen).

At this point in the interview, Marsha admitted: “We didn’t check for desirability in a simple way. We should’ve done that. We went building right away”. What she means is that more than often startups start building a product, instead of checking upfront whether customers would be interested. A way of doing this could be a smokescreen test, where you simulate that the solution is ready, to gauge interest.

Jumping to building an MVP might look like an error. However, this decision was not made without any thought. It was, as it turns out, made on inaccurate data. One developer said that he can probably have an MVP ready by the end of the week.” If we use a web app approach we can shorten development time to 3 days”, he said. Unfortunately for the team, it turns out it was much longer than that.

The point of this story is not to blame this developer. I’ve seen this happening before when I was working at a mature platform having 100 employees. I was in an innovation team, where we needed to import 1000 contacts in a new solution. We could’ve done this with a simple database export & import, taking up some manual work but at most two hours of work. The developer said he could build an API in a day or two, saving a lot of time of manual work on the long run. This sounded good, yet the API took two weeks in total, hindering crucial testing time for the solution we were developing. Estimating uncertainties in product development is hard, especially in new environments. That’s why agile software development is so popular, assuming you can’t possibly know your unknown unknowns. Marsha trusts her team, and if my developer says 3 days I would have no direct reason not to believe him. On top of that, a test with an MVP has much more detailed data than a smokescreen test would.

The lingering of high-quality data persuaded the team to build something. Big surprise (at least for the team), building a video-call tool wasn’t as easy and 3 days turned into 3 weeks. During this period, whenever they were testing, it turned out that it was hard for two people to have a stable video connection within their web app. After some time, a goal of success was set: If 80% of the video-calls make a stable connection, we are good to launch

To get there, the developer tried different approaches, such as build-from-scratch solutions to API solutions (Jitsi if you are curious). When I asked Marsha how often launch was postponed, she laughed as I discovered a little secret, and admitted: about 5 times. Frustration ensued. So far, nothing unusual in software development. After the 5th trial of their MVP, they got past the 80% stable connection mark.

Get ready for the soft launch

The team went from conception to building to launch. All this I type under the heading of the second iteration. When is an iteration an iteration? It’s an ever long discussion. Within their technical development of the product, they made numerous iterations towards a working MVP. I personally like to include customer contact within the definition of an iteration, and that was not happening until their launch.

The team was quite frustrated at that point with the process, they longed for some evidence that proved this energy was not wasted. The team used a soft launching strategy, where you slowly increase the number of users that could get access to the new feature. They decided to launch on April 4, to a segment of their active customers. In the morning, 600 people got a push message leading to a detailed message.

And then it was 20:30 on the opening night. The involved team members anticipated the numbers. People started dragging into the virtual speed date room. Some matches happened, some calls were made. On the back-end, some smoke appeared. Let’s look at the numbers to get a clear overview and increase our understanding of the results.

Of 564 who received that push message, 280 read that chat, 66 appeared online. 60 people had a match (30 matches in total). Out of those 60, 22 (11 matches) actually had a stable video call, 36% stable connection rate. The technical success rate they tested for, 80%, was not reached by a stretch. Besides the technical issues, 66 people interested with a high match rate was promising.

How did the team interpret these results? Marsha tells us: “We did not have any benchmark of performance. We were pleased with the 66 people that were online. It’s a start, it takes time for people to get used to it. The technical problems were fixable, we moved forward.”

Third iteration: Medium launch to hard launch

Medium launch: All the single ladies

The next step Marsha called the ‘medium launch’ to 1500 customers. “We believed that we were delivering value. We got messages from people that were not in the soft launch segment asking: ‘Why didn’t I get a link to the speed dates?’” This suggested some kind of virality, in the sense that people were referring other people to it. Simply said, evidence after the soft launch was not against them, yet also not highly convincing. Fixing the video issues was their key focus, addressing a big issue from the soft launch in order to launch to a bigger chunk of their users.

I asked Marsha what they were looking for, or measuring, in terms of evidence. “We were looking for growth in usage numbers. Also, we wanted to see if people were satisfied with the service.”

A couple of days into the medium launch, the data showed a growth in their stable connection rate. Their work payed off. The data also showed an imbalance in genders which they encountered before on the second night of the soft launch. About 75% was male, 25% was female. Almost all females matched, while a big part of males didn’t. Arguably the worst experience was for anyone to wait in that virtual room for 15 minutes and get no match.

In order to learn from qualitative data, they interviewed 3 people for every phase of the funnel (Figure 8) over the phone, totalling 15 calls. The male participants confirmed the pain of waiting and getting no match. During the calls, they did learn that males liked the concept, saw it as fun, but did it in setting with roomies on the couch. This made it awkward for some of the ladies, mentioned some of the females. For the ladies, there was a lot of anxiety in joining. “During corona, I don’t really do my make-up, do I need to dress up for these 15 minutes?” Some said it felt awkward for them: “I’m not good at video calls.” Women complained that they didn’t know what to do after a video speed date. “And then what? Back to chatting? Then we are back to Tinder”, one customer said.

So, there were objections, to say the least. But was it unsuccessful? It’s not always black and white. One customer said: “We had a video call of two hours afterwards were we played games and connected. We definitely exchanged numbers and aim to see each other in the future.” Stories like these have an emotional touch to them, making it harder to value them in a numerical sense. It’s easy to argue that this is a success story, and it was not the only one. The question in the startup was not anymore whether there was success. The question was is this successful enough to pursue?

From hard launch to hard exit

In preparation of the hard launch, the team focused on increasing the likelihood of a good experience. For that, they needed to tackle the complaints about males not getting matched. A feature was developed that enabled one person to get multiple speed-dates during the 15 minute time slot. “In this way, women could be ‘reused’”, Marsha giggles, as this term sounds a bit pejorative. The hard launch with the new feature happened, yet match rates for males were disappointing again (Figure 9), resulting again in bad experiences.

Internally in the team, people were getting tired with this new proposition. Marsha said: “At some point, I didn’t care anymore. I just wanted to push the hard launch. Go hard or go home.” And so they pushed to all the 4500 active users (hard launch) a message in the morning.

Enormous amounts of effort went in, but results weren’t a home-run yet. When I showed a draft of this article to CEO Joris, he commented on my wording in the absence of a home-run as “You are being very gentle.” Looking at the data amount of users and the growth they hoped for, you get a bleak image (Figure 10). A similar pattern as with the medium launch emerged: a peak and a decline. Not the longed for growth.

Last iteration: First hand experience on kill day

The team looked at the numbers next to the qualitative feedback and couldn’t ignore anymore that this road was going to nowhere. This was not the growth they were looking for. The targets they had set was 10% week on week growth, growth as a proxy metric for satisfaction, and as Figure 10 shows, growth has been absent for all three launches.

To say goodbye, one last session was organised on Friday, April 24th. Marsha recalled that one of the comments she got during the feedback calls from females was: “I want to do it, but not today, maybe later”, postponers she called them. Marsha identified with her, as she was one of the postponers herself. She figured that maybe this last session the pressure will convince them and something magical will happen. On this last session, the team was against better judgement open for a wonder to happen, to get that spurt they were looking for all along.

“This doesn’t work, who built this!?”

A special twist was on this last day: postponer Marsha joined in that session and got to use the product she built herself, along with a slight increase of women that session. Using your own product is a great experience in general. Not because it works per se, mainly because you learn so much. In her case, she was matched with 3 men. One caveat, her matches didn’t know she was the founder. And that helped Marsha to see how customers experienced the new solution first hand. One man said to her: “This doesn’t work, who built this!?”

After this goodbye session, the team pulled the plug on the new proposition. It was conceived and killed in less two months, it was live for about 20 days. There are many organisations, small and especially big, that take much longer to learn. In that sense, the efforts of this team are worth praising, as they eventually stopped pushing something that didn’t work.

Reflections by the team

After doing the interview, and typing this, I still was wondering how Marsha and the rest of the team reflected on this. I found myself wondering what initial goals they set for the product to achieve for the customer; asking myself whether we can explain the lack of adoption from there. I’m a big fan of the Job to be Done framework. If you are not familiar with Job to be Done (JTBD), I really suggest watching this 5 min video by Clayton Christensen (R.I.P.), who coined the term.

Marsha, familiar with the framework, said they didn’t define a job to be done upfront, but can reconstruct their intentions. She distinguishes that their pre-corona JTBD was functional: Get users on more dates, faster. After corona, the JTBD turned more emotional: Experience the thrill of dating again. And she mentions, when she was queueing in the online virtual room, she felt that thrill as her heartbeat rose.

I asked her, being a bit critical, why in all the goal metrics I didn’t see customer satisfaction as a central driver, but rather growth? In the interview, it didn’t come up all too organically. Marsha immediately recognises this and acknowledges that it was not in their scope.

Probably fuelled by the corona anxiety and time pressure, they focused on keeping them engaged. But they didn’t start at the customer’s needs and problems. Right away, they drafted a solution for a job to be done that was not formulated from customer input. By this, a shifted ensued from fixing the customers problems to fixing the startup’s problems. She reflects: “We should’ve started with the users.” In that way, a solution with higher likelihood of longevity could’ve been crafted.

On the road to publishing this paper, Marsha forwarded the team the draft of this article. Overall they felt, apart from some minor details and numbers that needed correcting, that it represented their journey accurately. It allowed Joris (CEO) to look back. He wished to reflect on the divide that happened within the team. “Don’t let your team become divided. It’s important to both give room for strategic experimentation and be strategically aligned. This is hard.” On top of that, he threw in this quote: “Go where your customers are going, not where the already are. We weren’t looking ahead properly. Due to the changing situation we just built something for now, but not really for the future.” Philip (CFO) adds to this: “Take some time to strategise how your service will change during a crisis rather than immediately build a rubber lifeboat when you know it will only last for a month.”

My take

So, what did we see here? We see a team whose startup was performing well. Due to the rapid changing environment, the team was hungry for staying relevant and sustaining the previously achieved growth. Uncertainty about the situation, such as the length of the lockdown, drove the team to make a fast decision.

By this, they lost their customer centricity and sense of strategy. It seemed they temporarily forgot that they got that growth by realising customer value. The new proposition was a solution with mixed interests from the start, firmly biased towards the startup itself, rather than the customer. It was not sustained by a deeper, researched understanding of their customers.

For a big part, I believe this explains why the solution wasn’t adopted in masses, which the data reflects. Not building a proposition around customer needs lowers the likelihood of adoption. The intended value, which is delivered when the product is used, should be in the core of the proposition based on the found (latent) needs from customers. It wasn’t there.

Their attempts to generate more value by analysing what happens in the funnel by phoning customers were sound. E.g., to improve the experience by increasing the male match rate is a logical step, nonetheless, evidence shows to no avail. Consequently, as customers kept perceiving it as not valuable, they didn’t return. From the point of view of their customers, it remained an engagement gimmick rather than the desired product for their (dating) needs.

Furthermore, an elaborate MVP approach with errors in development time estimations and technical difficulties delayed the time to launch. This hindered the team to learn sooner that this solution wasn’t a home-run. As the team reflected already, smaller steps should’ve been made. In its turn, these hick-ups shaped a cumbersome process which didn’t help with the team dynamics and shows us the importance of clear alignment on goals and proper communication.

On top of that, it didn’t help that life during corona is an ever-changing context, including as rapidly changing customer needs. New attitudes, restrictions or loosening of rules can render an entire iteration useless before it’s released. We saw this happen to some extent to this team in the first iteration. Combine this with a solution that was not born to win is a perfect recipe for failure.

This is my honest conclusion. The killing of the project is theirs. They made mistakes and acknowledged them. They are human, after all. Not any type of human. On the contrary, I see an energetic, talented team with a great drive, showing true grit in their approach. I will not be surprised if this team makes it in one way or another. What their home-run will be, however, only their customers can tell.

What’s next for Breeze?

While their rubber lifeboat was sinking, they were crafting a new plan. This was before the last speed date round, which said something about their trust in that last round. On April 19, Project Maywire was started. Or at least, the Slack channel was created. In my follow-up interview with Breeze, Marsha ran me through their new approach and strategy for running Breeze during corona. It appears that they’ve learned tremendously from their previous iterations, such as starting with identifying customers emerging (latent) needs, crafting a lengthier strategy, quicker feedback loops, shorter development times, and so on. That, combined with the results of their subsequent iterations, is worth an article on its own in the future.

I want to thank Breeze for their openness about their process and data and especially thank Marsha for her time with the interviews and gathering of this data.

Thanks for reading.

Enjoyed the read? Please like or share, if you want to see more of this! Did I miss anything? Please comment on what you take away from this article.

Do you know a startup with a story on a failed iteration?

I’m a researcher and looking for startup stories of failed iterations. Do you know any startup that had a failed iteration? E-mail me at j.coelen@tudelft.nl or drop me a message/DM me on Twitter @Coeluh.