Last week I published a piece on how past behaviour contains more truth than speculations about the future.

Two people sent me intriguing comments, focusing on a nuance that I didn’t address in that piece. It created a starting point for a little essay.

This format is an experiment, please let me know with voting (bottom) if you like it.

Re: The past holds (more) truth

Read the comments:

“[you bring a ] negative perspective to interviewing. I think the questions you put here sure, but you can ask way better questions about the future that could elicit underlying values and needs.

You just blow directly past that. Nuance your story”

“Very important topic, but I would partially agree with your negative consideration of questions about the future.

True that speculating the past is the key for a deeper understanding of present events, true that you can't ask very specific and practical questions about the future because it's a plural and uncertain realm.

But it's also true that it's important to understand how the past changed the users' mindset, their way of hoping, of dreaming, of planning their lives.

And actually, this is the ultimate goal of interviewing people for design purposes. To understand this you need good questions too.”

Both have a very similar critique: I didn’t talk about the aspirations, dreams, values of customers. Based on my previous article, you could interpret it as these entities are not valuable to innovation processes.

That was not my intention. These future-oriented entities are extremely important to grasp. Think about the customer’s goals—jobs to be done—as I often like to talk about.

This is about two strategies to identify these more abstract elements in the customer landscape. In the previous article, I identified one strategy: focusing on the past.

Those elements hold a lot of truth. But it’s not the only way to make sense of the user. Inquiring about the future is a way that can reveal nuggets of insight.

Future schmuture

What is the future? It depends on who you ask, e.g. some philosophers believe the future and now are not very different.

At least for now, let’s assume that the future is some undefined temporal moment ahead of us that is yet to happen. What elements of the future are important for innovators?

Aspirations and goals

Let’s start with aspirations and goals. Asking about the aspirations and goals of a user is not a bad thing. When I did innovation consulting, I learned that asking questions of this nature are very helpful:

“What does success look like to you?”

or

“When are you satisfied with this project?”

This invites the user to think about and paint a picture of the end result. This inherently is speculation. So we can tell it’s not true yet. If we would be able to tell if it is true, there would be no project, as the speculated state would be similar to today.

We can’t tell whether this speculated state is the appropriate state or not. However, from this speculated state you can learn a lot from and about the user. What does the user seem to value? What do the users say they wish to achieve?

Don’t always copy-paste

Now comes the caveat, how literally should we take those conjectures?

Think about politics. Some people vote for harsher penalties on crime. Harsher penalties on crimes don’t always have an effect on crime. Yet quite some people desire this for any crime.

The question is if you should copy-paste the desires you find 1 on 1 for your project. Should you copy the mechanism ‘harsher penalties’ or should you listen and learn that people like less crime as a desired outcome.

Insert ‘faster horses quote by Henry Ford’ (which he never said)

Learn about values via co-creation

If you want to learn more about these values, you can consider co-creation, a design method where you invite the users (or other stakeholders) to put on their design hats and design along.

Here, you use the design process to see what elements seem important for the user. By looking at the outcomes of this process, you can deduce which values the user prioritises.

And sometimes, definitely not always, you can even copy the solutions.

Example: My neighbourhood in Amsterdam allowed residents to design and submit plans to get grants to make changes to public areas. Submissions included the creation of more green with threes, adding benches or installing a petanque court.

Most of these submitters probably aren’t city planners. But, they could still design solutions for themselves, capturing their values, dreams and aspirations. Seems to work.

So when should you follow and when should listen for deeper values?

In the end, you are a doctor

Note that the users’ values aren’t the holy grail or the only value. The residents in my neighbourhood might value thousands of trees and social housing projects. But the municipality’s treasure chest is finite. That’s going to put a hold on a lot of initiatives.

The best analogy I learned from Professor Dirk Snelders, who was mentoring me in my graduation project. He imagined the designer/innovator/entrepreneur as a doctor and the customer as the patient.

What’s best for the patient? The doctor will investigate you and (hopefully) prescribe the right medicine or procedure. Patients sometimes desire certain medicine. Doctors don’t like that.

Sometimes, the medicine doesn’t exist yet and you need to create something new. And you can ask your patient to think along, but in the end, you are the doctor.

The patient is not the doctor

This hints at a view that most people don’t know what’s good for them and you—the superior innovator—does.

It comes with a dash of ‘You think you want this, but you need that’. To be fair, a doctor usually is more knowledgeable than the patient.

Except for when the patient had googled his symptoms. Then the patient basically skipped 10 years of education and experience, obviously.

Figuring out when to listen to whom is one of the most important skills in innovation processes.

If you listen to your user too much, you will forget about the needs of other stakeholders such as your company that needs to make money or the municipality’s treasure chest.

There are also thousands of founders that added every feature their customers asked for and went bankrupt.

On the other hand, there are countless examples of founders building products that nobody wanted. If you only listen to yourself, your product will not match the needs of the user.

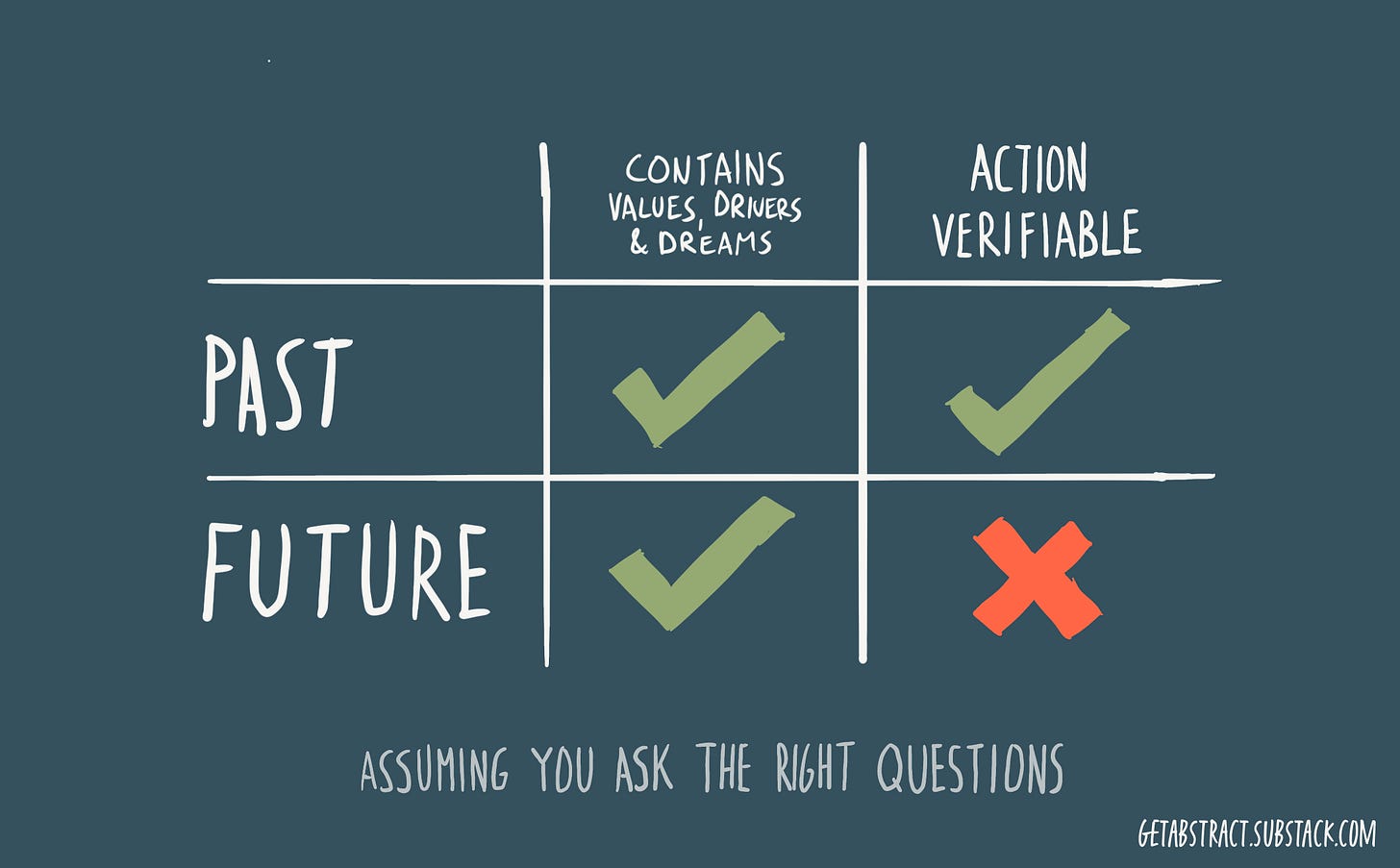

The updated diagram

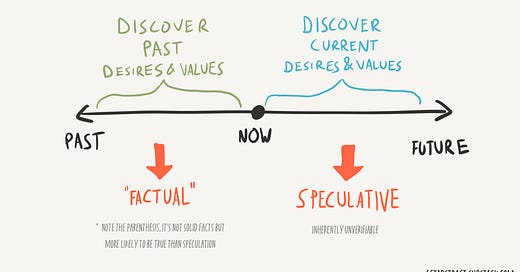

For the past desires, you can learn about whether those desires turned into action. For the future desires, you don’t know yet if it will turn into action.

That for me is the big difference between the two. Something you should take into account and influences the truth value of statements.

Two catches. With the wrong questions, you can get faulty data on anything. And then everything is untrue. Furthermore, you could suffer innovator’s bias, not really listening and just confirming your beliefs.

So, what about truth?

So this turned into a little essay about the role of the innovator and ended with the balance between listening to and overruling your patient.

It started out with the truth. I still believe that past behaviour holds truth and by that value. This doesn’t rule out that future speculations hold value as well.

It’s not two sides of the same coin though. It’s inherently different. Because there are quite some things I want to say about truth, knowledge and science, I’m saving that for a different piece.

Also, this piece is getting long and I need more time to organise my thoughts because truth and knowledge inherently get abstract.

How was this article?

Great - Good - Meh

If you vote you can win nothing. How about that?

Hi Jeroen, we met over a zoom meeting about a week ago. Your articles provide great additional insights and implementable actions! Thanks, just thought to drop by and say hi as your new subscriber :)) - Shuying